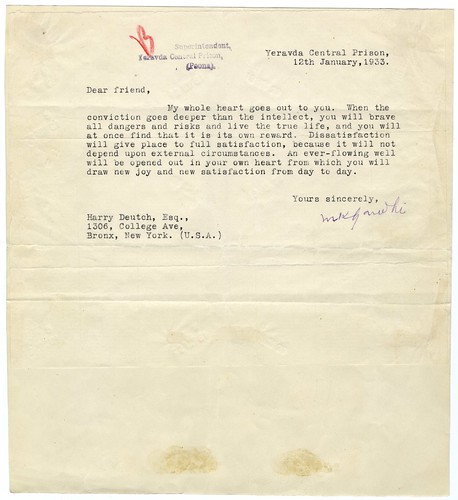

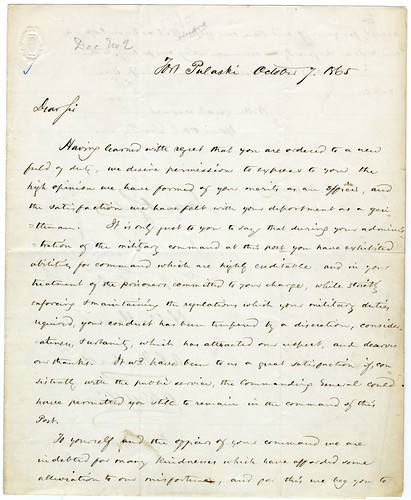

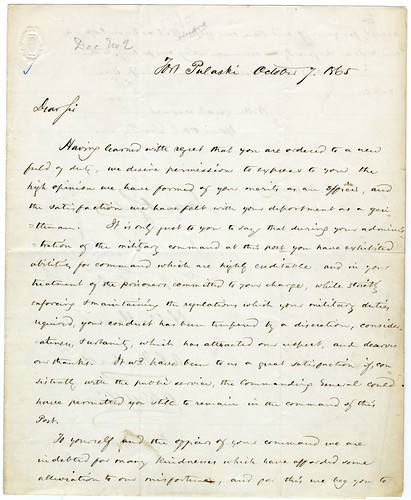

Fort Pulaski October 7. 1865Dear Sir Having learned with regret that you are ordered to a new field of duty, we desire permission to express to you the high opinion we have formed of your merits as an officer, and the satisfaction we have felt with your deportment as a gentleman. It is only just to your to say that during your administration of the military command at this post you have exhibited abilities for command which are highly creditable, and in your treatment of the prisoners committed to your charge, while strictly enforcing & maintaining the regulations which your military duties required, your conduct has been tempered by a distraction, considerations, & urbanity, which has attracted our respect, and deserves our thanks. It wd have been to us a great satisfaction if, consistently with the public service, the commanding General could have permitted you still to remain in the command of the Post. To yourself and the officers of your command we are indebted for many kindnesses which have afforded some alleviation to our misfortunes, and for this we beg you to accept for yourself and them our respectful acknowledgments; and to do us the favor of communicating our feelings of them.Our best wishes follow you in your future career. With great respectYour obt servtsMajor C.W. Manning U. S. A.[signed:]James A. Seddon J. A. Campbell G. A. Trenholm H. M. Mercer A. G. Magrath A. K. Allison D. L. YuleeIn this letter, CSA (Confederate States of America) statesmen - including the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Treasury, two governors, and a senator - express their favorable opinion of Major C.W. Manning (they probably meant Major William C. Manning). At the time, Manning commanded the 103rd U.S. Colored Troops, who were stationed as guards at Fort Pulaski where the statesmen were being held as prisoners after the end of the Civil War. Manning was Sergent Major of the 1st Massachusetts Volunteers from 1861 to 1863, which was present at the Second Battle of Bull Run (but did not participate) and was stationed at Maryland Heights near Harper’s Ferry until 1863. Manning was then 1st Lieutenant Adjunct of the 35th U.S. Colored Troops before becoming Major of the 103rd. After the civil war, Manning continued his military career until he retired for disability in 1899.1The statesmen remark on the humanity of their treatment while imprisoned at Fort Pulaski, despite the previous camp conditions. Prisoners were starved at the prison camp while it was under the command of Col. Philip P. Brown, Jr. Brown’s goal was to “make the fort the model military prison of the United States,” and he was noted for his humanity.2 However, the orders he made for supplies, including clothing, blankets, food, and fuel, were ignored. He fed prisoners out of garrison supplies until December 1864, when a starvation ration was imposed during the cold winter months. Eighteen prisoners died and most others suffered from scurvy before the fort was ceded to the District of Savannah as part of Savannah’s surrender to Sherman.Manning’s unit, which was organized at Hilton Head in March, was stationed at Fort Pulaski shortly after these events occurred, from June of 1865 to April of 1866. Most of the Confederate statesmen who composed the letter were initially imprisoned in April or May.3 In a letter dated August 21, 1865, the same statesmen wrote to Manning detailing their cooperation with the terms of their detainment:

Fort Pulaski October 7. 1865Dear Sir Having learned with regret that you are ordered to a new field of duty, we desire permission to express to you the high opinion we have formed of your merits as an officer, and the satisfaction we have felt with your deportment as a gentleman. It is only just to your to say that during your administration of the military command at this post you have exhibited abilities for command which are highly creditable, and in your treatment of the prisoners committed to your charge, while strictly enforcing & maintaining the regulations which your military duties required, your conduct has been tempered by a distraction, considerations, & urbanity, which has attracted our respect, and deserves our thanks. It wd have been to us a great satisfaction if, consistently with the public service, the commanding General could have permitted you still to remain in the command of the Post. To yourself and the officers of your command we are indebted for many kindnesses which have afforded some alleviation to our misfortunes, and for this we beg you to accept for yourself and them our respectful acknowledgments; and to do us the favor of communicating our feelings of them.Our best wishes follow you in your future career. With great respectYour obt servtsMajor C.W. Manning U. S. A.[signed:]James A. Seddon J. A. Campbell G. A. Trenholm H. M. Mercer A. G. Magrath A. K. Allison D. L. YuleeIn this letter, CSA (Confederate States of America) statesmen - including the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Treasury, two governors, and a senator - express their favorable opinion of Major C.W. Manning (they probably meant Major William C. Manning). At the time, Manning commanded the 103rd U.S. Colored Troops, who were stationed as guards at Fort Pulaski where the statesmen were being held as prisoners after the end of the Civil War. Manning was Sergent Major of the 1st Massachusetts Volunteers from 1861 to 1863, which was present at the Second Battle of Bull Run (but did not participate) and was stationed at Maryland Heights near Harper’s Ferry until 1863. Manning was then 1st Lieutenant Adjunct of the 35th U.S. Colored Troops before becoming Major of the 103rd. After the civil war, Manning continued his military career until he retired for disability in 1899.1The statesmen remark on the humanity of their treatment while imprisoned at Fort Pulaski, despite the previous camp conditions. Prisoners were starved at the prison camp while it was under the command of Col. Philip P. Brown, Jr. Brown’s goal was to “make the fort the model military prison of the United States,” and he was noted for his humanity.2 However, the orders he made for supplies, including clothing, blankets, food, and fuel, were ignored. He fed prisoners out of garrison supplies until December 1864, when a starvation ration was imposed during the cold winter months. Eighteen prisoners died and most others suffered from scurvy before the fort was ceded to the District of Savannah as part of Savannah’s surrender to Sherman.Manning’s unit, which was organized at Hilton Head in March, was stationed at Fort Pulaski shortly after these events occurred, from June of 1865 to April of 1866. Most of the Confederate statesmen who composed the letter were initially imprisoned in April or May.3 In a letter dated August 21, 1865, the same statesmen wrote to Manning detailing their cooperation with the terms of their detainment:“It is understood that in consideration of this parole we are to enjoy the liberty of the island - with the exception of the wharves when boats or vessels are there - during daylight, and the liberty of the main works at all hours; that we are not to forward or receive mail or express matter - other than proper mess supplies - without it has previously been submitted to the commanding officer at the post for inspection.”4

Another account describes the living conditions during their imprisonment:“The prisoners had cots on which they sat and slept. Morgan [Trenholm’s son-in-law] said they could see and smell the tide ebb and flow beneath the planks of the building. From prison, Trenholm wrote long letters home. He reported that the officer in command, Major William C. Manning, was doing everything that could be reasonably expected.”5

Yet despite these unfavorable living conditions, the statesmen were pleased with the command of the post and found their imprisonment to be generally humane. This is likely, in part, due to an overwhelming sense of relief that, as high-ranking officials of the secession movement, they were not being tried for treason. Despite a serious call from Northerners for severity in the treatment of the Confederates, neither Lincoln nor Johnson planned to punish the South for secession. In his own version of Reconstruction, Lincoln had planned to provide amnesty for most of the the South in order to speed up the process. In December of 1863 Lincoln declared that “a full pardon is hereby granted to them and each of them, with restoration of all rights of property, except as to slaves, and in property cases where rights of third parties shall have intervened, and upon the condition that every such person shall take and subscribe an oath” of loyalty to the United States.6Johnson formulated a policy somewhat less lenient than Lincoln’s. A Tennessee native who himself owned slaves, Johnson particularly detested the southern aristocracy, and so proclaimed that exceptions to the amnesty policy included landowners with property wealth of $20,000 or more, as well as the high ranking civil and military officials of the Confederacy. These men--including the statesmen imprisoned at Fort Pulaski--were required to apply to Johnson himself for pardon. About 15,000 applications were sent to Johnson in the following weeks and months, now known as the Confederate Amnesty Papers.7 Johnson was decidedly lenient, pardoning about 13,500 of these in the year after war's end. He received much criticism for his leniency and was accused of harboring Southern sympathies.The statesmen were detained at Fort Pulaski until specifically released by order of President Johnson or Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. The release of John Campbell and George Trenholm, ordered on 11 October 1865, was done with the reasoning that they “have made their submission to the authority of the United States and applied to the President for pardon under his proclamation.”8 Per the conditions of their parole, they were required to remain in their home states until their pardon was granted.

The men who signed this letter were likely the most notable to be held at Fort Pulaski under Union control.

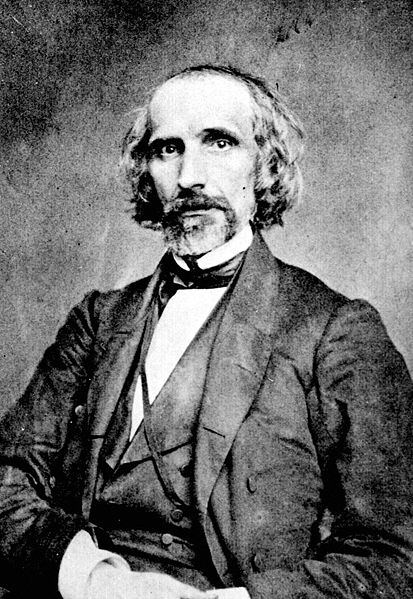

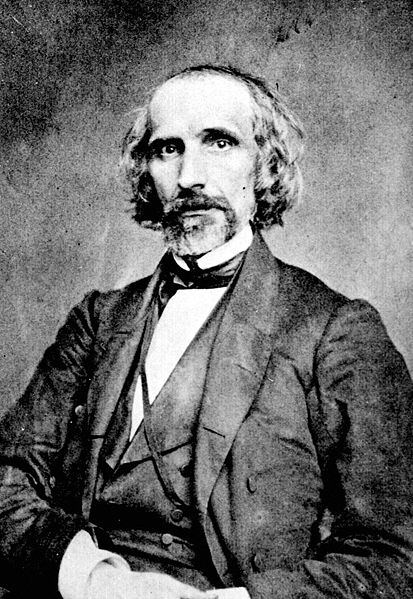

James Alexander Seddon (pictured above) attended the Peace Conference held in Washington, DC in 1861, which attempted to reunite the States and avoid war, where he “did his best to scuttle the peace process.”9 He was a member of the Confederate States Provisional Congress and, upon the resignation of Thomas Randolph and being a close friend of President Jefferson Davis, was appointed Secretary of War for the Confederacy on November 20, 1862. He spent most of the war in bad health but was unable to return home to Virginia because of Union occupation. Seddon was arrested in May and kept at Fort Pulaski for seven months. He died on August 19, 1880.

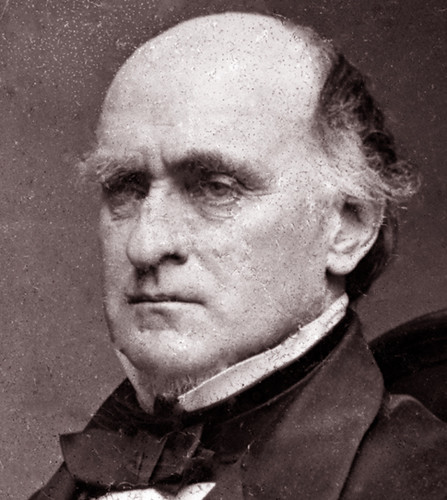

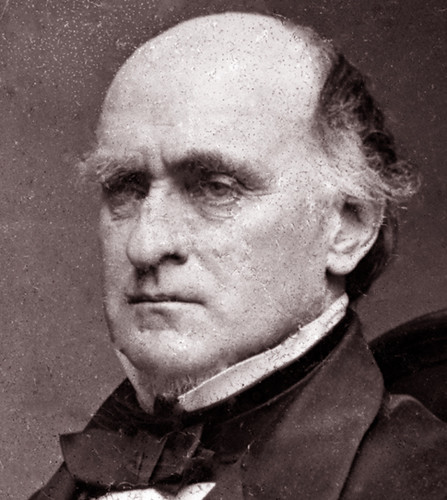

John Archibald Campbell (above) was a Justice of the Supreme Court from 1853 to 1861. Initially opposed to southern secession, he resigned his position as Justice upon learning of the Union reinforcement of Fort Sumter, believing this to be a display of aggression. He was appointed Assistant Secretary of War in 1862--a position he held for the rest of the war, acting as assistant to three different Secretaries of War. He was arrested in May and held until October 1865; he was paroled four days after the date on this letter. Campbell died March 12, 1889.

George Alfred Trenholm was a wealthy Charleston shipbuilder; during the war he oversaw the construction of the Confederate ironclad Chicora, which was later commanded by Manning and Magrath’s correspondent William Gaillard Dozier. Trenholm was appointed Secretary of the Treasury in July of 1864, and resigned on April 27, 1865, fleeing south after the fall of Richmond. He was replaced by John Reagan, who held the position for thirteen days before his and Davis’ capture in Irwinville, GA on May 10th. Trenholm himself was slowed in his escape by illness, and was captured at Fort Mill, SC in May. He was paroled with Campbell in October, and died on December 10, 1876.

Before the Civil War, Hugh Weedon Mercer was an artillery officer in the Savannah militia. Initially in command of Fort Pulaski, he rose quickly in prominence after the war began, and was promoted to commander of the District of Georgia, one of the loudest proponents for enlisting blacks in the ranks of the Confederacy. He served briefly in Tennessee before returning to Savannah as commander of the 10th Battalion. He left Savannah during Sherman’s takeover, and was arrested and detained at Fort Pulaski shortly thereafter. Mercer died on June 9, 1877 in Germany.

Andrew Gordon Magrath was a Harvard-educated lawyer centered in South Carolina. He’d been opposed to the secession movement of 1852, and he served as a Federal District Judge until November of 1860, when he traded his position in for South Carolina’s Secretary of State in December of that year. In December 1864, Magrath was elected governor of South Carolina, and served in this position until his arrest on May 25, 1865. He was charged with treason by General Gillmore on May 14 along with the governor of Georgia and Florida Governor Abraham Allison, with whom he was imprisoned at Fort Pulaski. The charge of treason was later revoked. Magrath died on April 9, 1893.

Abraham Kurkindolle Allison served as a Florida senator to the Confederacy from 1862-1864. After the suicide of Governor John Milton on April 1, 1865, Allison was sworn in. He resigned six weeks later in anticipation of the Union occupation of Tallahassee, but was arrested on June 19th and detained at Fort Pulaski. Allison died on July 8, 1893.

David Levy Yulee was a Jewish lawyer who represented Florida first in the United States Senate, and then in the Confederate Congress. He was imprisoned at Fort Pulaski for nine months after the war’s end. He died on October 10, 1886.

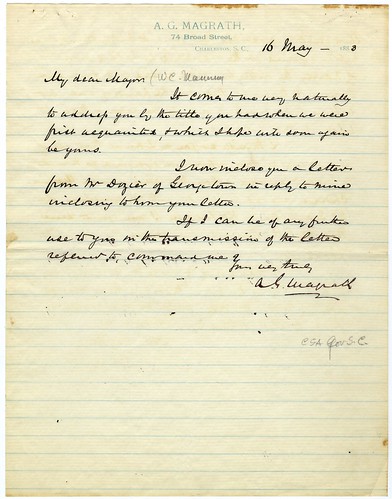

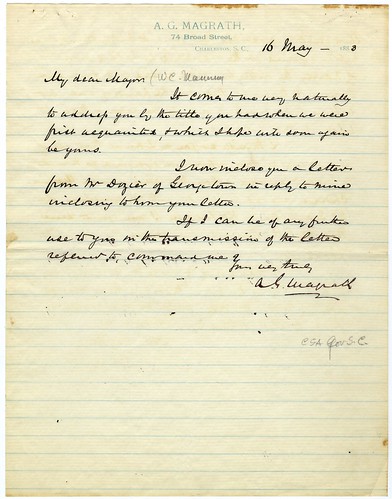

A second letter in in the Littlejohn manuscript collection is a part of subsequent correspondence between Major Manning and one of the statesmen who so highly praised him in 1865--Andrew Gordon Magrath. Magrath is offering his assistance to Manning, with whom he has apparently kept touch for almost 20 years.

16 May 1883

My dear Major.

It comes to me very naturally to addres [sic] you by the title you had when we were first acquainted, and which I hope will soon again be yours.

I now inclose you a letter from Mr. Dozier of Georgetown in reply to mine inclosing to him your letter.

If I can be of any further use to you in the transmission of the letter referred to, command me.

Yours very truly

A. G. Magrath

The man whom Magrath speaks of is William Gaillard Dozier, a naval officer who was at one time the lieutenant commanding officer of the CSS Chicora, a prominent ironclad built by Manning’s one-time captive Trenholm. Dozier, like the other statesmen, had to personally apply for pardon to President Andrew Johnson, though he was not required to serve time in prison.

Not much else can be found about Manning. After the Civil War, he remained in service to the United States Army serving in various capacities. He retired in 1886 for disability with the rank of major, but was brevetted the rank of Captain in 1890 for his “gallant service” against Apache resistance in 1872, where Manning and his unit launched a guerrilla assault against an Apache rancheria, killing 11 men and capturing 6 women and children.10 From what little is recorded about Manning, he seems to have been accorded great esteem by those who knew him. A Confederate lieutenant and four privates who were captured by Manning’s unit in 1862 described Manning as “brave, dashing and gallant a young officer as can be found in the Union Army.”11 One might wonder what about Manning’s character made him so appealing to members of the Confederacy, and further, what circumstances led Manning and the Confederate statesmen to stay in touch for so many years. This strange, enduring relationship between Manning and his prisoners warrants more historical exploration.

-- Stephanie Walrath '12 and Hannah Jarrett '12

1. List of officers of the army of the United States from 1779 to 1900, embracing a register of all appointments by the President of the United States in the volunteer service during the civil war, and of volunteer officers in the service of the United States, William H. Powell, ed., (New York: L.R. Hamersly & co., 1900), p. 452. http://www.archive.org/stream/listofficers00powerich#page/452/mode/2up

2. Ralston B. Lattimore, Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia, (Washington: National Park Service, 1961), p. 40.

3. Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1959).

4. Fred C. Ainsworth and Joseph W. Kirkley, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899), p. 723. Hereafter Official Records.

5. Ethel Trenholm Seabrook Nepveaux, George A. Trenholm, Financial Genius of the Confederacy, His associates and his ships that ran the blockade, (Anderson: The Electric City Printing Company, 1999), p. 162.

6. Freedman and Southern Society Project, “The Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction,” http://www.history.umd.edu/Freedmen/procamn.htm

7. Ludwell H. Johnson, Division and Reunion: America 1848-1877, ( New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1978), p. 198

8. Official Records, p. 763.

9. Charles F. Ritter and Jon L. Wakelyn, Leaders of the American Civil War: a biographical and historiographical dictionary, (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1998), p. 334.

10. Gregory F. Mincho, Encyclopedia of Indian wars: Western battles and skirmishes, 1850-1890, (Missoula: MountainPress Publishing, 2003), p. 261.

11. Thomas E. Parson, Bear Flag and Bay State in the Civil War: the Californians of the Second Massachusetts Cavalry, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc.), 2001, p. 73.