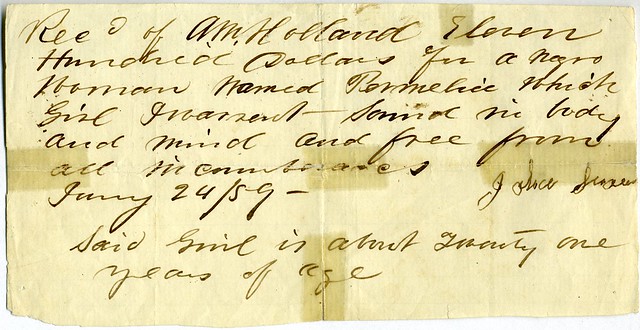

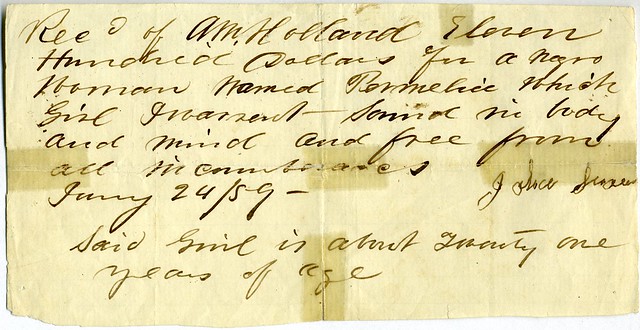

This item is a receipt for the sale of 21-year-old Permelia to A.M. Holland by John Susan[?] for $1100.

The full text reads:

“Rec’d of A.M. Holland Eleven Hundred Dollars for a Negro Woman Named Permelia which Girl I warrant sound in body and mind and free from all incumberances [sic]

Jany 24/59 –

[signed] John Susan[?]

Said Girl is about Twenty one years of age”

It is difficult to know much for certain about the people concerned in this transaction. The illegibility of the seller’s signature, perhaps due to his semi-literacy, prevents us from knowing his name for certain.

However, research reveals that an Adolphus Milton (A.M.) Holland (b. Georgia) married a Mississippi woman in 1858 in Harrison County, Texas and was living with her in Rusk County by 1860.

Knowing this, from a social and economic standpoint the purchase of a slave woman for domestic duties makes some sense and lends weight to the assertion that this was the same A.M. Holland.

It seems that A.M. Holland served as a Confederate soldier through at least 1863, until he was presumably disabled.

The fate of 21-year-old Permelia, though, is lost to history — for now. If she survived the war period, Permelia would have been about 27 years old by 1865, and may turn up in the 1870 Federal Census.

(This is a web essay reflecting an item from the Littlejohn Collection on display in the lobby of the Sandor Teszler Library until 22 April 2013.)