Camp near Mickey’s

April 4 1862

General:The Cavalry & Infy of the enemy attacked Colo Clanton’s regiment which was posted as I before informed you about 500 or 600 yards in advance of my lines. Colo Clanton retired & the enemy’s cavalry followed until they came near our Infy & Arty when they were gallantly repulsed with slight loss.

Very Rsply,

W.J. Hardee

Maj Genl

Genl Braxton Bragg.Chief of Staff

This letter, handwritten in pencil by Confederate Major General William Joseph Hardee to General Braxton Bragg only two days before the Battle of Shiloh commenced, summarizes a chaotic and enigmatic event which very nearly started Shiloh before either party was prepared.

(Map of Shiloh National Military Park. Courtesy of the National Park Service. Full size here.)

(Map of Shiloh National Military Park. Courtesy of the National Park Service. Full size here.)The Confederate advantage in the days before Shiloh lay in their knowledge of the Union position and the Union’s failure to anticipate an attack. Even though Confederate General Johnston’s initial plan was to march on April 4th, Union General Grant thought that a Confederate attack was unlikely; just hours before being attacked on the morning of April 6th, he sent a telegram to his superior General Halleck asserting that "I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack being made upon us.”30 The Union commanders failed to realize that the skirmish referred to here, in this letter by Hardee, signaled a far worse attack to come.

In the first week of April, both Union and Confederate troops had set up camp in and around Hardin, Tennessee. After crossing the Tennessee River, Grant spread his troops out around Pittsburg Landing, covering several miles along the western shore of the river and creating several encampments around Shiloh Methodist Church (a Hebrew word ironically meaning “Place of Peace,” after which the battle is named). Meanwhile, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston stationed his Army of the Mississippi around Corinth, about twenty miles southwest of Grant’s position.

In the first week of April, both Union and Confederate troops had set up camp in and around Hardin, Tennessee. After crossing the Tennessee River, Grant spread his troops out around Pittsburg Landing, covering several miles along the western shore of the river and creating several encampments around Shiloh Methodist Church (a Hebrew word ironically meaning “Place of Peace,” after which the battle is named). Meanwhile, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston stationed his Army of the Mississippi around Corinth, about twenty miles southwest of Grant’s position.

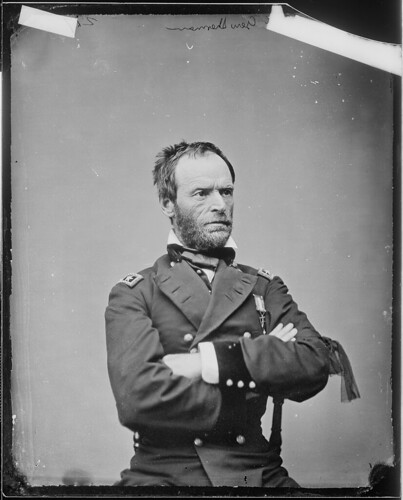

(At left, Major General William T. Sherman, commanding the 5th Division of the Army of West Tennessee. At right, Major General William Hardee, corps commander in the Army of the Mississippi.

For a clearer understanding of who was involved in this battle and on which side, click here or here.)

Yet in the days preceding battle, it was not unusual for units on the fringes of their encampments to edge relatively close to the enemy. The incident described in this letter by Major General William Hardee began when a group of Confederate soldiers were noticed in the fields within a quarter mile of a Union picket post on the morning of April 4th. A report was filed to Union General Sherman that there were armed rebels hunting for lunch within close range, but upon closer inspection Sherman decided that the rebels were “nothing more than a reconnoitering party,” and was not alarmed.2

Seemingly secure, Union troops under General Ralph Buckland began to drill around the contested area that afternoon, until shots were heard and Buckland’s eight picket guards were discovered to be missing, “either lost in the woods or captured by marauding Southern cavalry.”3 Companies B and H of Buckland’s 72nd Ohio then went to find the missing soldiers, and the remainder of Buckland’s infantry retreated back to Shiloh Church. But when Companies B and H failed to return from their search mission, Buckland assembled a hundred men and returned to the picket line, beyond which they discovered that Major Leroy Crockett had been captured and Company H was engaged in combat with nearly 200 Confederate cavalry.4

Hearing sounds of battle, Sherman ordered reinforcements to ride in under Major Elbridge Ricker. Ricker’s 5th Ohio Cavalry forced the retreat of Colonel James Holt Clanton’s regiment over a hill, but when a few of Ricker’s cavalry “surged over the hill...[they] reined up in shock. Ahead of them was a long line of gray infantry with three field guns.”5 Chaos ensued. The Confederates fired their field guns, startling Ricker’s horses and causing a frenzy in which two Confederates and one Union soldier were killed before the Buckland’s swift retreat. The five remaining Ohio cavalrymen who had witnessed the line of Confederates reported, surprised, that it consisted of 2,000 men and multiple batteries.6

After the debacle had ended, it seemed as though “both sides had been bloodied and appeared content to break off the contest.” 7 Sherman, meanwhile, had assembled multiple regiments for reinforcement and, despite the capture of a handful of prisoners, was irate that Buckland’s advance “might have drawn the entire army into a fight before it was ready.” 8

Hardee’s mention of the “slight loss” sustained by the Union included the young Major Leroy Crockett, who was captured in his pursuance of Clanton’s unit. The loss of Crockett seemed to have been of no object to Sherman, and even Hardee fails to mention this ranked prisoner of war in his note to Braggs. It appears that Crockett has been buried in the massive heap of Civil War History, and very little remains on record regarding Crockett other than his promotion to Colonel in November of 1862 and his death little more than a year later. After his capture, Crockett was interrogated and (apparently voluntarily) relayed information that indicated to the Confederate Generals that the Union was still completely unprepared for an attack (as indicated in Grant’s telegram). Crockett confessed that “They don’t expect anything of this kind back yonder”9 and upon seeing the breadth of the Confederate encampment, exclaimed, “Why, you seem to have an army here; we know nothing of it.” 10

This brief incident failed to alarm Sherman; moreover, it is unknown whether Grant was ever notified about the near-battle or the capture of Crockett for informational purposes. It appears that, having lost very few, Sherman did not take the skirmish very seriously and was more annoyed by the inconvenience than concerned about what it might portend. The Confederates, on the other hand, were delighted to have learned that, despite delaying their attack, they had retained the element of surprise. Until the morning of the attack, Sherman remained adamant that the skirmish was a fluke, and ignored the advice of commanders who warned him of an impending strike. It was April 5, the day before Shiloh began, that Sherman replied to one of his subordinates who expressed concern that the Confederates were near: “Take your damned regiment back to Ohio. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth.”11

For a clearer understanding of who was involved in this battle and on which side, click here or here.)

Yet in the days preceding battle, it was not unusual for units on the fringes of their encampments to edge relatively close to the enemy. The incident described in this letter by Major General William Hardee began when a group of Confederate soldiers were noticed in the fields within a quarter mile of a Union picket post on the morning of April 4th. A report was filed to Union General Sherman that there were armed rebels hunting for lunch within close range, but upon closer inspection Sherman decided that the rebels were “nothing more than a reconnoitering party,” and was not alarmed.2

Seemingly secure, Union troops under General Ralph Buckland began to drill around the contested area that afternoon, until shots were heard and Buckland’s eight picket guards were discovered to be missing, “either lost in the woods or captured by marauding Southern cavalry.”3 Companies B and H of Buckland’s 72nd Ohio then went to find the missing soldiers, and the remainder of Buckland’s infantry retreated back to Shiloh Church. But when Companies B and H failed to return from their search mission, Buckland assembled a hundred men and returned to the picket line, beyond which they discovered that Major Leroy Crockett had been captured and Company H was engaged in combat with nearly 200 Confederate cavalry.4

Hearing sounds of battle, Sherman ordered reinforcements to ride in under Major Elbridge Ricker. Ricker’s 5th Ohio Cavalry forced the retreat of Colonel James Holt Clanton’s regiment over a hill, but when a few of Ricker’s cavalry “surged over the hill...[they] reined up in shock. Ahead of them was a long line of gray infantry with three field guns.”5 Chaos ensued. The Confederates fired their field guns, startling Ricker’s horses and causing a frenzy in which two Confederates and one Union soldier were killed before the Buckland’s swift retreat. The five remaining Ohio cavalrymen who had witnessed the line of Confederates reported, surprised, that it consisted of 2,000 men and multiple batteries.6

After the debacle had ended, it seemed as though “both sides had been bloodied and appeared content to break off the contest.” 7 Sherman, meanwhile, had assembled multiple regiments for reinforcement and, despite the capture of a handful of prisoners, was irate that Buckland’s advance “might have drawn the entire army into a fight before it was ready.” 8

Hardee’s mention of the “slight loss” sustained by the Union included the young Major Leroy Crockett, who was captured in his pursuance of Clanton’s unit. The loss of Crockett seemed to have been of no object to Sherman, and even Hardee fails to mention this ranked prisoner of war in his note to Braggs. It appears that Crockett has been buried in the massive heap of Civil War History, and very little remains on record regarding Crockett other than his promotion to Colonel in November of 1862 and his death little more than a year later. After his capture, Crockett was interrogated and (apparently voluntarily) relayed information that indicated to the Confederate Generals that the Union was still completely unprepared for an attack (as indicated in Grant’s telegram). Crockett confessed that “They don’t expect anything of this kind back yonder”9 and upon seeing the breadth of the Confederate encampment, exclaimed, “Why, you seem to have an army here; we know nothing of it.” 10

This brief incident failed to alarm Sherman; moreover, it is unknown whether Grant was ever notified about the near-battle or the capture of Crockett for informational purposes. It appears that, having lost very few, Sherman did not take the skirmish very seriously and was more annoyed by the inconvenience than concerned about what it might portend. The Confederates, on the other hand, were delighted to have learned that, despite delaying their attack, they had retained the element of surprise. Until the morning of the attack, Sherman remained adamant that the skirmish was a fluke, and ignored the advice of commanders who warned him of an impending strike. It was April 5, the day before Shiloh began, that Sherman replied to one of his subordinates who expressed concern that the Confederates were near: “Take your damned regiment back to Ohio. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth.”11

Despite the initial advantages of the Confederates, however, the second day of battle at Shiloh proved disastrous. Johnston had suffered a fatal wound and, with his death, the coordination of the Confederate line fell apart. Their retreat back toward Corinth on the night of April 7 was followed only a little way past Shiloh Church before the spent Union soldiers returned to their own camps, declaring an anticlimactic end to this devastating battle.

- Stephanie Walrath '12

1 Timothy T. Isbell, Shiloh and Corinth: Sentinels of Stone (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), 30.

2 Larry J. Daniel, Shiloh: The Battle That Changed the Civil War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 133.

3 Daniel, 134.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Daniel, 135.

8 Ibid.

9 Stephen Berry, House of Abraham (New York: First Mariner Books, 2007), 109.

10 Daniel, 125.

11 David G. Martin, The Shiloh Campaign: March-April 1862 (Cambridge: De Capo Press, 2003), 90