[TRANSCRIPTION:]

[recto]

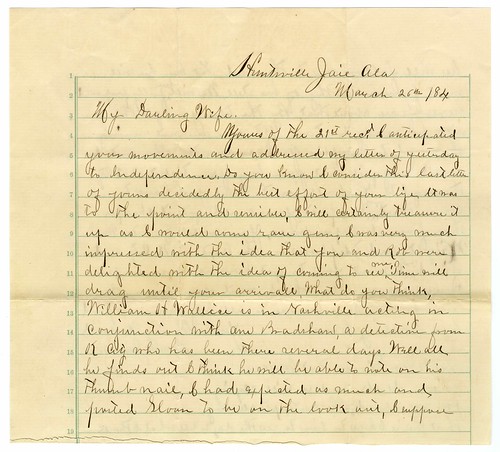

Huntsville Jail Ala.

March 26th/84

My Darling Wife.Yours of the 21st rec’d I anticipated your movements and addressed my letter of yesterday to Independence. Do you know I consider this last letter of yours decidedly the best effort of your life. It was to the point and remember, I will certainly treasure it up as I would some rare gem, I was very much impressed with the idea that you and Rob were delighted with the idea of coming to see me. Time will drag until your arrival, what do you think William H. Wallace is in Nashville there acting in conjunction with one Bradshaw, a detective from Kansas City who has been there several days. Well, all he finds out I think he will be able to note on his thumbnail, I had expected as much and posted Glover to be on the lookout, I suppose

[verso]

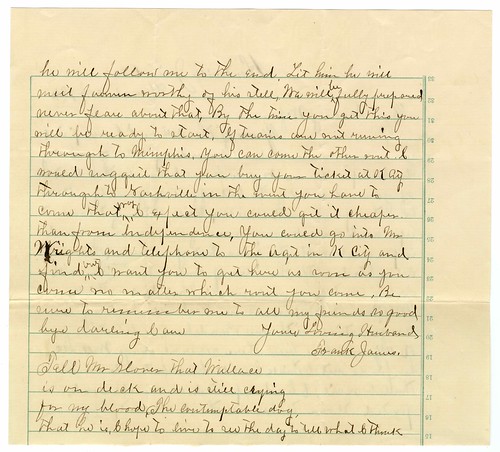

he will follow me to the end. Let him he will meet fervor worthy of his still. We will be fully prepared never fear about that. By the time you get this you will be ready to start, if trains are not running through to Memphis. You can come the other route. I would suggest that you buy your ticket at Kansas City through to Nashville in the event you have to come that way, I expect you can get it cheaper than from Independence, you can go into Mr. Wrights and telephone to the agent in Kansas City and find out. I want you to get here as soon as you come no matter which route you come. Be sure to remember me to all my friends, so good bye darling, I am

Your loving husband

Frank James

Tell Mr. Glover that Wallace

is on deck and is still crying

for my blood, The contemptible dog,

and that he is, I hope to live to see the day to tell what I think.

Your loving husband

Frank James

Tell Mr. Glover that Wallace

is on deck and is still crying

for my blood, The contemptible dog,

and that he is, I hope to live to see the day to tell what I think.

On March 26, 1884, Alexander Franklin “Frank” James wrote his wife from Huntsville, Alabama jail. He was awaiting trial for the Muscle Shoals, AL robbery of March 11, 1881. James was accused of robbing paymaster general Alexander Smith of $5,200. In his letter he expresses longing to see his wife, Annie Ralston James, and encourages her not to worry about the threats coming from the prosecution, which was led by William H. Wallace.

A notorious outlaw and member of the James-Younger gang, Frank James had been in prison since October 4, 1882, when he voluntarily surrendered to Missouri Governor Thomas T. Crittenden. James handed Crittenden his holster and said “Governor Crittenden, I want to hand over to you that which no living man except myself has been permitted to touch since 1861, and to say that I am your prisoner.”1 His surrender occurred six months after his brother and partner in crime, Jesse James, was assassinated by Robert Ford.

After his arrest, Frank James was moved to a jail cell in Independence, MO. His reception and treatment was hardly that of a dangerous criminal. He was allowed to wave at crowds from the back of the train that transported him. A reception dinner was held for him once he arrived in Independence. Supposedly, bankers offered to post a $100,000 bail for his release. In jail, Frank was allowed books, a comfortable chair, visitors, and whatever else he requested. He felt confident that he would not be convicted since the crimes he was accused of were committed years before. In the event that he was convicted, James was certain he would pardoned by the Governor. And in a bizarre turn of events, Frank James managed to be acquitted or pardoned for every crime he was accused of committing.2

While James was being held in Independence, he was charged with the the murder of Chicago detective Whicher (1874), the Independence bank robbery and murder of John Sheets (1869), the Blue Cut train robbery (1881), and the Winston train robbery and the murder of conductor William Westfall and passenger Frank McMillan (1881). James was acquitted on all accounts because the jury was not persuaded by the testimony of the prosecution’s primary witness Dick Liddell (also spelled “Liddil”), a former member of the James-Younger gang. The eloquent closing statements of John F. Phillips and Charles P. Johnson succeeded in convincing the jury that there was not enough evidence linking James to the crimes. By this point, James had won the sympathy of most Missourians due to his Confederate loyalties and his Robin Hood-like desire to avenge his family and former members of the Quantrill guerrillas for the crimes committed against them during and after the Civil War.3

During the war, James was a member of the Quantrill guerrillas, a group of pro-Confederate bushwhackers in Missouri. James’s involvement in the group had a significant impact on his criminal career. Many of James’s later crimes were in response to the way his friends and family were treated during the war. On one particular occasion, Unionists questioned Zerelda Samuel, James’ mother, about her son’s whereabouts and the location of the Quantrill guerrillas. They pushed her around, despite the fact that she was pregnant at the time. When she refused to give up any information, they tortured Dr. Reuben Samuel (James’s step-father) by hoisting him four times from the branch of a tree. He also refused to give away any information about his step-son’s whereabouts. Desperate for information, the Unionists chased and beat Jesse, Frank’s younger brother. In the end, Zerelda and Reuben were put in jail and Jesse’s hatred for Unionists increased, leading him to join his brother as a member of the Quantrill guerrillas.4

After the war, Frank and Jesse were harassed by members of the community because they were members of the Quantrill guerrillas. The Pinkerton Detective Agency was known to be involved in hunting the brothers throughout their criminal career. Allegedly, the Pinkertons were involved in bombing the James-Samuel house one night. The family heard a noise and went to the kitchen to discover that the west side of the house was on fire. Reuben saw a bomb and tried to shovel it into the fireplace. He was too late. The bomb went off, killing Archie James and injuring Zerelda (she lost her right arm). The continuous harassment of their family and friends can be seen as one of the leading motivations behind Frank and Jesse’s criminal behavior.5

The James brothers’ motivation for the Independence Bank robbery and murder of John Sheets was to avenge the murder of their friend Bloody Bill Anderson. Supposedly, the brothers had mistaken Sheets for Major S. P. Cox, whose troops had ended Bloody Bill Anderson’s career in 1864. Others believed that the robbers thought Sheets had somehow been involved in killing Anderson.6 As for the Winston train robbery and murder of William Westfall, Jesse James believed Westfall had been aboard the train that carried the Pinkertons to the bombing of the James-Samuel house. Similarly, the criminals announced that their attack on the train at Blue Cut was in response to Chicago and Alton Railroad’s participation in the reward offer for their capture.

After James was acquitted and released in Independence, he was immediately arrested again; this time for the Muscle Shoals robbery in Alabama. He was moved to a jail in Huntsville, AL, and on April 17, 1884, Frank was tried. Like the trail in Independence, Liddell failed to convince the jury that his testimony was reliable. Furthermore, the defense called to witness several people who claimed to have seen James in Nashville at the time of the robbery, which supported James’s alibi that he had been staying in Nashville under the name B.J. Woodson when the crime took place in Alabama. He was again found not guilty.

Upon his release, James was immediately arrested for the Rocky Cut robbery of July 7, 1876, but Governor Crittenden pardoned him. For good.

James spent the next thirty years doing various jobs; he was a shoe salesman, a ticket-taker at a theater, and a telegraph operator. Right before his death, he supported himself and his family by giving tours of the James farm in Missouri for 25 cents. He died at age 71, leaving behind his wife and son.

A notorious outlaw and member of the James-Younger gang, Frank James had been in prison since October 4, 1882, when he voluntarily surrendered to Missouri Governor Thomas T. Crittenden. James handed Crittenden his holster and said “Governor Crittenden, I want to hand over to you that which no living man except myself has been permitted to touch since 1861, and to say that I am your prisoner.”1 His surrender occurred six months after his brother and partner in crime, Jesse James, was assassinated by Robert Ford.

After his arrest, Frank James was moved to a jail cell in Independence, MO. His reception and treatment was hardly that of a dangerous criminal. He was allowed to wave at crowds from the back of the train that transported him. A reception dinner was held for him once he arrived in Independence. Supposedly, bankers offered to post a $100,000 bail for his release. In jail, Frank was allowed books, a comfortable chair, visitors, and whatever else he requested. He felt confident that he would not be convicted since the crimes he was accused of were committed years before. In the event that he was convicted, James was certain he would pardoned by the Governor. And in a bizarre turn of events, Frank James managed to be acquitted or pardoned for every crime he was accused of committing.2

While James was being held in Independence, he was charged with the the murder of Chicago detective Whicher (1874), the Independence bank robbery and murder of John Sheets (1869), the Blue Cut train robbery (1881), and the Winston train robbery and the murder of conductor William Westfall and passenger Frank McMillan (1881). James was acquitted on all accounts because the jury was not persuaded by the testimony of the prosecution’s primary witness Dick Liddell (also spelled “Liddil”), a former member of the James-Younger gang. The eloquent closing statements of John F. Phillips and Charles P. Johnson succeeded in convincing the jury that there was not enough evidence linking James to the crimes. By this point, James had won the sympathy of most Missourians due to his Confederate loyalties and his Robin Hood-like desire to avenge his family and former members of the Quantrill guerrillas for the crimes committed against them during and after the Civil War.3

During the war, James was a member of the Quantrill guerrillas, a group of pro-Confederate bushwhackers in Missouri. James’s involvement in the group had a significant impact on his criminal career. Many of James’s later crimes were in response to the way his friends and family were treated during the war. On one particular occasion, Unionists questioned Zerelda Samuel, James’ mother, about her son’s whereabouts and the location of the Quantrill guerrillas. They pushed her around, despite the fact that she was pregnant at the time. When she refused to give up any information, they tortured Dr. Reuben Samuel (James’s step-father) by hoisting him four times from the branch of a tree. He also refused to give away any information about his step-son’s whereabouts. Desperate for information, the Unionists chased and beat Jesse, Frank’s younger brother. In the end, Zerelda and Reuben were put in jail and Jesse’s hatred for Unionists increased, leading him to join his brother as a member of the Quantrill guerrillas.4

After the war, Frank and Jesse were harassed by members of the community because they were members of the Quantrill guerrillas. The Pinkerton Detective Agency was known to be involved in hunting the brothers throughout their criminal career. Allegedly, the Pinkertons were involved in bombing the James-Samuel house one night. The family heard a noise and went to the kitchen to discover that the west side of the house was on fire. Reuben saw a bomb and tried to shovel it into the fireplace. He was too late. The bomb went off, killing Archie James and injuring Zerelda (she lost her right arm). The continuous harassment of their family and friends can be seen as one of the leading motivations behind Frank and Jesse’s criminal behavior.5

The James brothers’ motivation for the Independence Bank robbery and murder of John Sheets was to avenge the murder of their friend Bloody Bill Anderson. Supposedly, the brothers had mistaken Sheets for Major S. P. Cox, whose troops had ended Bloody Bill Anderson’s career in 1864. Others believed that the robbers thought Sheets had somehow been involved in killing Anderson.6 As for the Winston train robbery and murder of William Westfall, Jesse James believed Westfall had been aboard the train that carried the Pinkertons to the bombing of the James-Samuel house. Similarly, the criminals announced that their attack on the train at Blue Cut was in response to Chicago and Alton Railroad’s participation in the reward offer for their capture.

After James was acquitted and released in Independence, he was immediately arrested again; this time for the Muscle Shoals robbery in Alabama. He was moved to a jail in Huntsville, AL, and on April 17, 1884, Frank was tried. Like the trail in Independence, Liddell failed to convince the jury that his testimony was reliable. Furthermore, the defense called to witness several people who claimed to have seen James in Nashville at the time of the robbery, which supported James’s alibi that he had been staying in Nashville under the name B.J. Woodson when the crime took place in Alabama. He was again found not guilty.

Upon his release, James was immediately arrested for the Rocky Cut robbery of July 7, 1876, but Governor Crittenden pardoned him. For good.

James spent the next thirty years doing various jobs; he was a shoe salesman, a ticket-taker at a theater, and a telegraph operator. Right before his death, he supported himself and his family by giving tours of the James farm in Missouri for 25 cents. He died at age 71, leaving behind his wife and son.

** The Littlejohn Collection at Wofford College has two other manuscripts pertaining to Frank James. They can be found here and here.

--Hannah Jarrett '12 and Becky Heiser '11

1 qtd. in Marley Brant, Jesse James: The Man and the Myth, New York: Berkeley Publishing Group, 1998, p. 239.

2 Michael J. Cronan, “Trial of the Century!: The Acquittal of Frank James,” Missouri Historical Review Vol. 1, Issue 2, January 1997, p. 134.

3 Cronan, p. 133-153.

4 Brant, p. 26-33.

5 Brant, p. 133-136.

6 William A. Settle, Jesse James was His Name: or, Fact and Fiction Concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977, p. 40.

2 Michael J. Cronan, “Trial of the Century!: The Acquittal of Frank James,” Missouri Historical Review Vol. 1, Issue 2, January 1997, p. 134.

3 Cronan, p. 133-153.

4 Brant, p. 26-33.

5 Brant, p. 133-136.

6 William A. Settle, Jesse James was His Name: or, Fact and Fiction Concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977, p. 40.

No comments:

Post a Comment