The Confederate States Patent Office began to take shape in the early months of 1861 after Jefferson Davis sent word to the Confederate Provisional Congress that the government was already receiving seventy patent applications a month. 1

Rufus Randolph Rhodes, who had experience in the U.S. Patent Office before secession, was appointed Commissioner of Patents, and he moved the patent records office from Alabama to Richmond, Virginia.2 The first Confederate patent was issued on August 1, 1861, and patents were issued regularly by the CSA Patent Office after that.3 The most famous invention patented by the CSA Patent Office was the Confederate ironclad ship Merrimac, which was designed by John Mercer Brooke.4

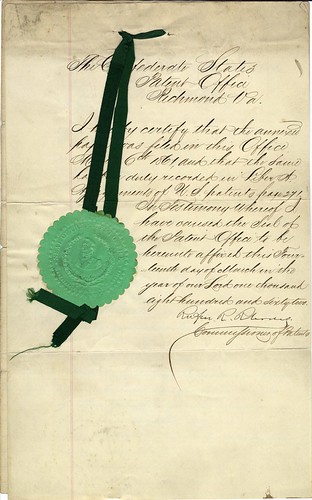

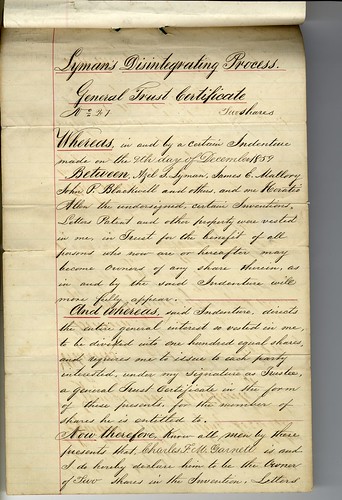

Above: An 1862 patent for Azel S. Lyman’s Disintegrating Process signed by Rufus R. Rhodes, Commissioner of Patents. Held in the Littlejohn Collection at Wofford College.

Azel S. Lyman’s Disintegrating Process was used for preparing flax, hemp, and other fibrous plants for textile purposes. The invention was acclaimed for its “ingenious application of the explosive power of steam to the separation of the fibers of all vegetable materials.”

To the agriculturist it presents a powerful inducement for to profitable account the vast area of western specially adapted to the growth of flax and hemp while it furnishes facilities for utilizing the thousands of tons of flax straw which have been and still are left as useless to rot the ground after the removal of the seed.5

Patents are granted by the government to inventors for a certain period of time. To acquire a patent, inventors must go through a application process, which includes a petition and various fees. The invention is then reviewed by government appointed patent examiners before being approved for a patent. A patent allows the inventor to “exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing into the country the patented invention for a period of time.” Essentially, patents secure a way for inventors to make money from their inventions. Abraham Lincoln stated that the patent system “added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius, in the discovery and production of new and useful things.” 6

Yet the CSA Patent Office does not appear to have granted very many patents during its short existence. Between 1861 and 1864, the CSA Patent Office only issued 266 (known) patents, which is a small amount when compared to the 16,051 patents issued by the U.S. Patent Office during that same period. That is, the number of patents the south granted was less than 10% of the national total. Does that mean the South lacked inventive genius?

The lack of southern patenting compared to Northern patenting has been used to argue several things about the state of the south before, during, and after the Civil War: (1) the south was agrarian, and therefore less likely to support new inventions and patents; (2) the south was not as educated as the north in terms of technology; and (3) the south lacked mills and other industry that fostered invention. H. Jackson Knight eliminates these possibilities as major factors because they do not hold up against the reality of the South during the Civil War.7

Knight offers other possibilities for the lack of southern patenting: (1) there was a lack of foreign immigrants in the southern states before the war, as compared to in the northern states; (2) the practice of agriculture in the south was a rural enterprise, and there was less motivation to patent any inventions; (3) there was a lack of highly developed communication and transportation, which made sharing information about inventions more difficult; and (4) there was the war itself and the uncertainty of government protection of inventions.8

In the south, patents were a secondary objective unless the invention could be used to help defeat the enemy. In fact, in 1861, 32% of patents issued by the CSA Patent Office fell under the category “Fire Arms and Implements of War.” One third of the patents in 1862, the year of Lyman’s Disintegrating Process, were for inventions for use in the war. Only one patent in 1862 is recorded to be for the “Manufacture of Fibrous Substances, Including Machines,” which is the category Lyman’s invention would fall under. (Knight doesn’t mention Lyman in his book, so it is unknown if he is referring to Lyman’s invention here.) 9

There is perhaps a more practical reason for the lack of southern patents. Rhodes noted that patent applications dropped during the second half of 1862 because “occupation of considerable portions of the Confederate States by the Union Army” meant that the clerical force of the CSA Patent Office was reduced. In fact, by the end of the war, there was only one examiner in the CSA Patent Office.10

Also, it is important to keep in mind that the CSA Patent Office burned down in April 1865 after Confederate forces set fire to the city during the evacuation of Richmond. In June, the U.S. Commissioner of Patents sent an examiner to recover any records of the CSA Patent Office, but he didn’t find anything. The only known surviving records of the CSA Patent Office are two partial ledger books, a few original patents (such as the one for Lyman’s invention), four Annual Reports of the Confederate Commissioner of Patents, and various other printed reports. 11

-- Hannah Jarrett ‘12

CITATIONS

1. Kenneth W. Dobyns, The Patent Office Pony: A History of the Early Patent Office, http://www.myoutbox.net/popch27.htm, p. 167.

2. H. Jackson Knight, Confederate Invention: The Story of the Confederate States Patent Office and Its Inventors, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011, p. 50.

3. Dobyns, p. 167.

4. Dobyns, p. 169.

5. The Friend, August 8, 1861.

6. Knight, p. 1.

7. Knight, pp. 73-74.

8. Knight, p. 90.

9. Knight, p. 122.

10. Dobyns, p. 168.

11. Dobyns, p. 169.

"Rufus R. Randolph, who had experience in the U.S. Patent Office..."

ReplyDeleteShould that be "Rufus R. Rhodes", or "Rufus Randolph Rhodes"?

Yes, thanks. This error has been corrected in the text.

Delete