“Do you want me to look a fright in the midst of Splendour?” she whispered, imagining John Quincy standing in front of her with a disapproving look.1

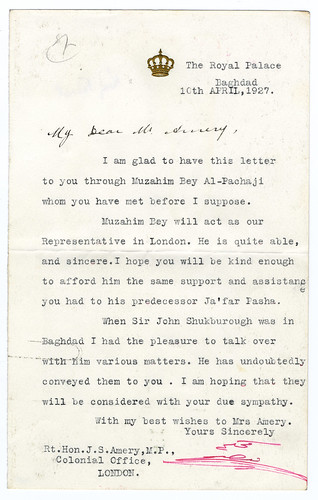

| This portrait of Louisa Adams was painted by Charles Robert Leslie in 1816 in London. |

The night before, when the Prussian Queen had offered her the rouge, John Quincy had insisted that she refuse. At first, Louisa had dutifully done as he commanded. She began to have second thoughts, though, when saw her reflection in a darkened window. Her face was rather pale. While John Quincy was occupied, she sought out the Queen and accepted her offer. After some convincing, she knew her husband would understand. She was, after all, the wife of the Ambassador to Prussia and the daughter-in-law of the President of the United States, and rouged cheeks were expected of her in Berlin’s court society.

Louisa stood up, checking herself one last time in the mirror. No one could deny that her brightened face livened her dull homemade dress. John Quincy walked into the room, and Louisa reached up to dim the light in an attempt to hide her face. Just as she thought she had escaped his notice, John Quincy pulled her close to the light. She saw the rage in his eyes as he demanded that she wash her face. But instead of complying, Louisa “with some temper refused.”2 In a surge of anger, John Quincy left for the party without her. But Louisa didn’t let that discourage her. With her face still decorated, she arrived at the party on her own and ended up making quite an impression on the king and queen of Prussia.

If Louisa ever regretted defying her husband, she never let it show. Based on her parents’ relationship, she believed “it was necessary for her own self-respect...to remind her husband from time to time that she was not the conventionally submissive helpmeet that middle-class Americans seemed to admire in their wives in the early nineteenth century.”3

Louisa’s childhood had been filled with encouragement and opportunity, which turned out to be both her blessing and her curse. Born in London in 1775 to an American father and an English mother, Louisa attended school in France, where she became so fluent in French that she had to relearn English when she returned to London. Since French was the language of diplomatic society at the time, Louisa was able to hold her own in the courts of Europe even though John Quincy would have preferred to control his wife’s tongue as much as possible.4

Louisa and John Quincy met and married in London in 1797. They were an unlikely pair from the start; everyone suspected that John Quincy would marry one of Louisa’s older sisters. Louisa, who “foresaw women taking a vigorous role, one of equal importance to that of men”5 was not the most obvious choice for a man like John Quincy, who, with his short temper and severity, was determined to bow to no woman.

Like many men during his time, John Quincy would tolerate only the most passive female, which would seem unlikely considering the relationship between his parents. With a mother like Abigail Adams, it would only seem logical for John Quincy to marry a woman like Louisa. But John and Abigail Adams had reservations about the Johnson-Adams marriage. In fact, Abigail thoroughly disapproved of her son’s wife at first, mostly because she judged Louisa as a foreigner and “anti-american.” With their son’s political career in mind, “they often fretted about [Louisa’s] ability...to measure up to the rigorous family standards.”6 Louisa eventually proved herself to her in-laws, and they welcomed her into their lives and hearts.

The same could not be said for John Quincy. As his parents grew more fond of Louisa, he grew more distant. Time would prove that John Quincy “never saw in marriage the partnership arrangement advocated by his parents....At heart he seemed to fear the opposite sex, and eventually most of his anxiety took the form of disregarding and disobeying his wife.”7

But the couple’s dysfunctionality was not the only thing to plague their marriage. Louisa had twelve pregnancies and seven miscarriages between her twenty-first and forty-second years, and as a result, “her health was wretched a great deal of the time....She once complained that ‘hanging and marriage were strongly assimilated.’”8

Despite everything, Louisa supported her husband’s political endeavors. In 1824, John Quincy refused to campaign for the presidential nomination. He expected to be nominated as “a reward for his many years of public service.”9 As a result, Louisa became his campaign manager. Louisa “curried to the right congressional wives, always ‘Smilin’ for the Presidency,’ calling cards in purse.... In the election year, she hosted dinners for sixty-eight congressmen. Every single Tuesday night between December and May, she held open house with fine wine, lavish food, and musical entertainment.”10 No doubt that John Quincy was fully aware of what his wife was doing for him, and we can only hope that he realized that without her he had little chance of being elected.11

If Louisa could have seen the future, though, she might not have worked so hard to get her husband into office. Her years as First Lady were the worst of her life. She noted that “the exchange to a more elevated station must put me in prison.” Furthermore, after he was elected president, John Quincy’s use for his wife ended. He became even more cold, demanding, and inconsiderate toward her, and once sniped, “There is something in the very nature of mental abilities which seems to be unbecoming in a female.”12

Louisa proved to be good at hiding her true feelings, though. Harriet Upton, in an illustrated piece for the November 1888 issue of Wide Awake, described Louisa as “enjoying an existence of ‘wooings and weddings, baby life and christenings and many frolics, long old-fashioned visits from relatives, quiet hours when the President read aloud.” The article pictured a first lady who, like all right-minded women, served in a man’s world.”13 In truth, Louisa spent most of her time alone and ignored, and she called the White House “her prison” and a place “which depresses my spirits beyond expression.”14

Louisa spent most of her time in the White House alone in her room. Over the years, she developed a deep depression and a breathing problem (her room was heated with burning anthracite coal, which caused choking and coughing). Louisa wrote that her depression “passes for ill temper and suffering for unwillingness and I am decried an incumberance unless I am required for any special purpose for a show or some political maneuver and if I wish for a trifle of any kind, any favor is required at my hands, a deaf ear is turned to my request. Arrangements are made and if I object I am informed it is too late and it is all a misunderstanding.”15

To combat her isolation and depression, Louisa ate chocolates obsessively and took to writing poems and satirical plays about the folly of society and the illnesses of females. She also began her autobiography, which she called Adventures of a Nobody.16 In short, Louisa was angry. She was angry about what she believed men were doing to humiliate women.17 A latent feminism emerged in her writing, which “was aroused in her bitterness over a world in which man controlled female, no matter how capable the female might be.” Louisa resented “that sense of inferiority which by nature and by law we [women] are compelled to feel and to which we must submit is worn by us with as much satisfaction as the badge of slavery generally, and we love to be flattered out of our sense of degradation.”18

To Dr. Thomas.

___

at note last night addressed to you

was by my pen indited [sic]:

Professional alone ‘tis true

By anxious doubt incited:

Your presence eased the laboring? thought

The note aside was laid

Before, with kind expression fraught

my compliment was paid

In justice then Dear Doctor now

The pen I quick resume,

Esteem and friendship to avow,

To love I cann’t presence -

Love such as Mother to her Son

With bond affection proffer’d;

Sprung from a grateful heart alone

with pleasure may be offer’d -

of deep respect assurance kind

no proof what’ere requires

Tis the conviction of the mind

that merit aye inspires;

This silly scrawl you must excuse

A laugh its best reward

The Sentiment do not refuse;

The lines their just reward

Louisa Catherine Adams

F. Street 25 Jan 1842

Above: Louisa Catherine Adams' poetry manuscript dated 1842, from the Littlejohn Collection at Wofford College.Following his term as president, John Quincy entered Congress and became involved in the anti-slavery movement, which resulted, finally, in the couple developing a sympathetic understanding for each other.19 Louisa spent her last years dedicated to the fight for freedom of slaves and women.20 Their mutual pursuit for equality at the end of their lives was the closest thing to a happy ending the couple had.Years after her death, Louisa’s grandson, Henry Adams, remembered thinking there was something exotic about his grandmother. He wrote that he liked “her gentle voice and manner; her vague effect of not belonging there [Boston], but to Washington or to Europe, like her furniture, and writing-desk with little glass doors above and little eighteenth-century volumes in old bindings labelled ‘Peregrine Pickle’ or ‘Tom Jones’ or ‘Hannah More.’ Try as she might the Madame could never be Bostonian, and it was her cross in life, but to the boy it was her charm.” Henry Adams knew little about his grandmother’s interior life, which had been, like many women of the time, full of severe stress and little pure satisfaction.21

| The F Street house near the White House was Louisa’s home during many of her years in Washington and the site of her death. Earlier, it had been the residence of Dolley and James Madison. The property remained in the Adams family until 1884. |

-- Hannah Jarrett ‘12

1. Boller, Paul F. Jr., “Louisa Catherine Adams 1775-1852,” Presidential Wives: An Anecdotal History, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 55.

2. Nagel, Paul C., The Adams Women: Abigail & Louisa Adams, Their Sisters and Daughters, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 170.

3. Boller 56.

4. Allgor, Catherine, “Louisa Catherine Adams Campaigns for the Presidency,” Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government, University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 161.

5. Nagel 161.

6. Allgor 161-162.

7. Nagel 164.

8. Boller 55.

9. Boller 57.

10. Anthony, Carl Sferrazza, First Ladies: The Saga of the President’s Wives and Their Power 1789-1961, New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1990, pp. 107.

11. Boller 58.

12. Anthony 108.

13. Nagel 3.

14. Boller 53.

15. Anthony 108.

16. Anthony 109.

17. Nagel 4.

18. Anthony 109-110.

19. Boller 54.

20. Anthony 111.