Frida Kahlo was born on July 6, 1907, to Guillermo Kahlo and Matilde Calderon. Guillermo was a well-known photographer, and the family was moderately wealthy; however, Frida would have a difficult and pain-filled life. She contracted polio at age eleven which crippled her right leg and left her with a life-long limp. At age eighteen, Kahlo was in a terrible crash between a local bus and a trolley. She broke her leg, spine, collarbone, and pelvis in the accident and was forced to spend months wrapped in casts and bedridden in hospitals and at her home. Before her accident Kahlo studied medicine at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (National Preparatory School) in Mexico City. While she was bedridden, Kahlo was able to devote large amounts of time to painting, and it was during this time that she painted several of her first self-portraits that she would later show to Diego Rivera. After asking Rivera to critique her work, the two fell in love and got married in 1929.1

Diego Rivera was a huge man both in stature and in importance. He stood over six feet tall and never weighed less than 300 lbs in his entire adult life. He was charismatic, passionate, innovative, and determined. “He not only achieved his goal of bringing art to the people of Mexico, but also brought the art of Mexico to the world.”2His art represented Mexico’s contribution to modern art. Rivera’s style was grand in scale and ideology and his murals portrayed scenes designed to inspire nationalistic and socialistic sentiments in the viewer. The most common themes involve the roles of indigenous groups in the history of Mexico and those of the worker in the development of the nation.3

Malu Block, Frida Kahlo, and Diego Rivera.

The pair resided in the United States from 1930 through 1933 so that Rivera could work on the commissions he received from various American businessmen and politicians. During those three years Rivera worked on a number of projects including murals in San Francisco, Detroit, and Manhattan. He was eventually fired from working on a mural in the new Rockefeller Center because he painted a portrait of Vladimir Lenin in the middle of the mural - a less than desirable choice in Cold War America. Rivera and Kahlo returned to Mexico, and Rivera finished his murals in the Palacio Nacional (National Palace) in Mexico City and in the Hotel del Prado, the home of one of his best-known works: “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park.”4

(For more Rivera paintings, click here.)

The Rivera-Kahlo marriage was a stormy one and was marked by infidelity on both sides. They divorced in 1939; however, by 1940, they remarried and remained married until Kahlo’s death in 1954. Kahlo was never able to have children, probably due to the accident during her teenage years, and she spent a lot of time in and out of hospitals, undergoing multiple surgeries for her chronic pain. Before she died, her right leg was amputated because of gangrene. Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, of either a blood clot or an intentional drug overdose.5

One of the houses where Rivera and Kahlo lived.

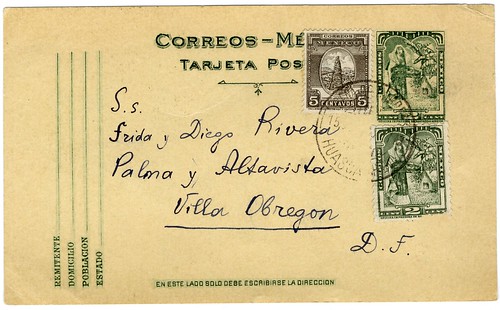

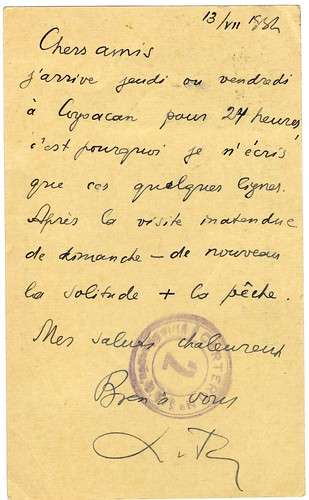

Throughout their lives Rivera and Kahlo were supporters and members of the Mexican Communist Party. They were vocal in their support, and both frequently used communist themes in their artwork. Their participation in the Communist Party created an opportunity for them to meet and house Leon Trotsky while he was in exile in Mexico City. When Joseph Stalin came to power in the Soviet Union, Trotsky fell quickly out of favor. He was exiled to Alma-Ata in Central Asia, but he escaped and fled to Turkey, then France, followed by Norway, and then eventually he found himself in Mexico in 1937. He had been invited to come to Mexico by the President Lazaro Cardenas and was welcomed by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo to Casa Azul, their home in Coyoacan, a province of Mexico City. Both Rivera and Kahlo were honored to have Trotsky stay with them, and they offered him and his family every protection they could provide. During his stay at the Kahlo home, Trotsky and Kahlo even had a love affair.6 His affair created tension within his own marriage, and he decided that he needed to get away from Kahlo and Rivera for a time. He went on a vacation to the countryside in July 1937. Frida made an unexpected trip to visit him; however, Trotsky refused to continue their affair. After this encounter he sent the following note addressed to Frida and Diego on July 13, 1937, which can be found in the Littlejohn Collection at Wofford College:

[translation and transcription]

I will arrive in Coyoacan Thursday or Friday for 24 hours; that is why I’m writing only a few lines. After Sunday’s unexpected visit - again solitude and fishing. My warm greetings.

Troksky lived in Mexico peacefully for some time. He had a fallout with Rivera in 1939 due to political differences, and he decided to move his family into a different house, although he remained in Coyoacan. Trotsky’s life was always in some danger, however, and there was an attempted assassination on May 24, 1940, when David Alfaro Siquieros fired over 200 shots into Trotsky’s home. The family escaped harm in that attack, but a second attempt proved successful. Ramon Mercader, a member of the Soviet secret police, broke into Trotsky’s home in Coyoacan and attacked him with an icepick on August 21, 1940.

“Mexican, shaped by disabilities, bisexual, inexhaustibly creative - all these ideas describe Frida Kahlo, but neither separately nor even together do they suffice to capture her spirit.”7 Frida’s personality is reflected in her artwork. Most of her paintings are autobiographical and followed the style called “mexicanidad.” This style rejected Western and aristocratic influences and instead focused on national folk culture. Accordingly she depicts herself in the traditional garb of the indigenous people of Tehuantepec using bright colors and a sense of fantasy. Kahlo described her work as “acid and tender, hard as steel, and delicate and fine as a butterfly’s wing, loveable as a beautiful smile, and profound and cruel as the bitterness of life.”8 Her artwork was popular around the world, and she had art shows in New York and in Paris. She only had one exhibition in Mexico shortly before she died. During her life, she was overshadowed by her husband, but her fame has only grown since her death, and now she is viewed by many as a feminist heroine.9

(For more Kahlo paintings, click here.)

Since the release of the 2002 film Frida, interest in Kahlo has revived. Her paintings have sold for millions of dollars. Madonna, the pop star, actually owns several originals. Some enthusiasts have begun to wonder if the image of Frida that is so appealing is in fact inaccurate, and the surge in interest and in biographies and other works has only served to further distort the image of the artist. Stephanie Mencimer, the editor of the Washington Monthly, argues that while most of Frida’s self-portraits portray her as a victim who could not have children and who was married to an unfaithful husband, the reality was that she never wanted children and she had her own extramarital affairs on a regular basis. Mencimer even goes so far as to say that many of Kahlo’s surgeries were unnecessary and were used to gain the attention of her husband and her acquaintances. Kahlo was not the Trotsky-supporter she seems to be in her biographies. In fact, Mencimer points out that after Trotsky’s assassination, Kahlo became a devout Stalinist.10 It is difficult to say whether Mencimer’s view of Kahlo or the artist-as-victim view is more accurate. Much of Kahlo’s life story has been constructed around her paintings, and Mencimer challenges the validity of this approach. Perhaps more evidence is needed to construct a well-rounded picture of Kahlo. Recently, Carlos and Leticia Noyola of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, announced in 2010 that they have a collection of Frida possessions: paintings, letters, diaries, clothing, and knick-knacks. The initial reaction of Kahlo experts was to declare the collection forgeries; however, a year later, the debate over the authentication of these items is still in full swing with little progress on either side.11 But perhaps the recently-discovered collection is exactly what is needed and can provide a new, more accurate glimpse into the life of Frida Kahlo.

- Becky Heiser ‘11

1 Tibol, Raquel. Frida Kahlo: An Open Life, trans. Elinor Randall. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993.

2 “Diego Rivera,” Contemporary Hispanic Biography, Vol. 2, Gale, 2002, Gale World History in Context, 23 June 2011.

3 "Rivera, Diego," The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Ed Ian Chilvers. Oxford University Press 2009 Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 27 June 2011

4 "Diego Rivera," Contemporary Hispanic Biography. As above.

5 "Frida Kahlo," Contemporary Hispanic Biography. Vol. 1. Gale, 2002. Gale World History In Context. 23 June 2011.

6 "Kahlo, Frida," The Oxford Dictionary of Art, Ed. Ian Chilvers, Oxford University Press, 2004, Oxford Reference Online, 23 June 2011,

7 "Frida Kahlo," Contemporary Hispanic Biography. As above.

8 “Kahlo, Frida" A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, Eds. Ian Chilvers and John Glaves-Smith. Oxford University Press, 2009, Oxford Reference Online, 5 July 2011.

9 Ibid.

10 Mencimer, Stephanie, “The Trouble with Frida Kahlo: Uncomfortable truths about this season’s hottest female artist,” The Washington Monthly, June 2002, http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2001/0206.mencimer.html#byline, June 29, 2011.

11 Yabroff, Jennie, “The Frida Fighters,” Newsweek, August 26, 2010, http://www.newsweek.com/2010/08/26/the-case-of-the-questionable-frida-kahlo-paintings.html, June 29, 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment