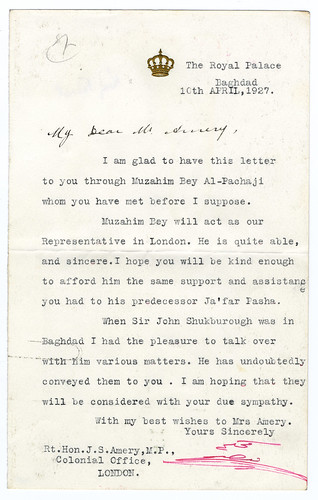

The Royal Palace

Baghdad

10th APRIL, 1927

My Dear Mr. Amery,

I am glad to have this letter to you through Muzahim Bey Al-Pachaji [sic] whom you have met before I suppose.

Muzahim Bey will act as our Representative in London. He is quite able, and sincere. I hope you will be kind enough to afford him the same support and assistance you had to his predecessor Ja’far Pasha.

When Sir John Shukburough was in Baghdad I had the pleasure to talk over with him various matters. He had undoubtedly conveyed them to you. I am hoping that they will be considered with your due sympathy.

With my best wishes to Mrs. Amery.

Yours Sincerely

[signed] Faisal

Rt. Hon. J.S. Amery, M.P.,

Colonial Office,

LONDON.

In this letter, King Faisal I introduces Muzahim al-Pachachi, Iraq’s new ambassador to Britain, to Leo Amery, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Faisal I, a Sunni Muslim and part of the Hashemite family, which descended from the prophet Muhammad, was born in 1885 in the city of Ta’if. He was destined for political involvement from birth; Faisal’s father, Hussein bin Ali, was the leader of the Arab Revolt of 1916, Sharif of the Holy City of Mecca, and later King of Hejaz. Faisal was elected to the Ottoman Parliament in 1913 before he joined his father and his British allies in the Arab Revolt to topple the Ottoman Empire.1

After World War I, the newly established League of Nations decided that government of the Middle East needed to be delegated to European powers. They redrew the borders of this region, in many cases ignoring long-standing ethnic and cultural groupings that had defined boundaries previously. The countries who were mandated to the European powers were classified as either A, B, or C, depending on the League’s perception of how autonomous the mandate should be. Both Class A Mandates, and theoretically granted the highest level of autonomy, Syria was mandated to France, and Iraq to Britain.

Because of the impressive and victorious nature of his leadership in the Arab Revolt that secured the city of Damascus for Arab control, Faisal was appointed King of Greater Syria in March 1919. Unfortunately, the League of Nations had other plans; France was granted its mandate for Syria in April, and in July, after a short-lived and unsuccessful resistance, Faisal was deposed and banished.

Britain, however, was interested in Faisal’s leadership. They admired Faisal’s dedication, diligence, and cooperation, traits that they sought in a ruler to maintain their mandate. They also believed that Faisal would be “moderate and that his reputation as an Arab figure of international stature would prove attractive within Iraq.”2 At the Cairo Conference in 1921, Faisal accepted Britain’s offer of kingship with the understanding that he would be allowed to work Iraq toward a state of independence. True to their word, the British set up treaties over a ten-year period that increased Iraq’s autonomy until, in 1930, they signed a treaty that would allow Iraq independence within two years.3

Faisal’s ambitions were broader than mere Iraqi independence, however; he was deeply devoted to the cause of pan-Arabism. He attempted to strengthen Middle Eastern ties to achieve this goal through appointment of ethnically and religiously diverse scholars, economists, and advisers to his cabinet. These appointees were Sunni and Shiite, Syrian and Iraqi. In 1925 Faisal successfully passed Iraq’s first Constitution. This constitution was in effect until 1958 when the monarchy was overthrown and the Hashemite family executed. Remnants of this constitution can be seen in Iraq’s constitution today.

Not much is known about Al-Pachachi, but he was the ambassador to Britain from 1927-1928 after serving two years in parliament. The previous ambassador, Jafar al-Askari, was Iraq’s first minister of defense and served twice as Iraq’s ambassador to Britain. He was taken prisoner by the British during WWI and later joined the British in the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans. Al-Askari and Faisal had a history long before the British crowned Faisal king of Iraq and even before Faisal had been elected King of Syria. Faisal and Al-Askari worked together in the Arab Revolt of 1918 with the British against the Ottoman empire, and when Al-Askari became military governor, he gained control of much of the conquered land in Syria. In February of 1919 he became governor of Aleppo. In this position he was described as “an able man...frank and broadminded...[with a] good angle of vision towards the problems of government.”4

Al-Askari’s family was of great importance in the development of Iraq; his brother-in-law, Nuri Pasha al-Said, was elected Prime Minister seven times, and served a crucial role in the evolution of British-Iraqi relations. Both were Arab nationalists who believed that cooperation with the British was paramount for the advancement of an independent Iraq. Both were also killed for their political work; Al-Askari during the coup of Bakr Sidqi in 1936, and Al-Said as a result of the July 14th Revolution of 1958 that toppled the monarchy Faisal constructed.

Faisal’s correspondent, Leo Amery, was the Secretary of State for the Colonies, overseeing the British mandates from the Colonial Office in London. Amery advocated a strong British presence in Iraq, arguing in the Cabinet in 1918 that “only actual possession of the Middle East before a cease-fire went into effect would enable the Cabinet to bring the region into the British orbit.”5 He expressed fear that without a strong hold in the Middle East, Germany might be able to capture this enviable slice of land, which contained the trade route to Asia. Amery held Zionist convictions, which likely influenced Faisal’s own Zionist sympathies. Faisal was exceptional in his religious tolerance; the Constitution he enacted in 1925 assures that “Complete freedom of conscience and freedom to practise the various forms of worship, in conformity with accepted customs, is guaranteed to all inhabitants of the country provided that such forms of worship do not conflict with the maintenance of order and discipline or public morality.”6

Iraq was admitted into the League of Nations in 1932. Faisal died of a heart attack in 1933 and didn’t get to experience much the independence he had created.7 But his contribution to the development of Middle Eastern autonomy lasted far beyond his twelve years in office.

- Stephanie Walrath '12 and Hannah Jarrett '12

References

1. David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (New York City: Avon Books, 1989), p. 113.

2. William L. Cleveland, A History of the Modern Middle East (Boulder: Westview Press, 2000), p. 203.

3. Ibid

4. Malcolm B. Russell, The First Modern State: Syria under Faysal, 1918-1920 (Minneapolis: Bibliothetic Islamica, 1985), p. 64.

5. David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (New York City: Avon Books, 1989), p. 364.

6. “The Constitution of the Kingdom of Iraq,” Part 1, Article 13.

7. David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (New York City: Avon Books, 1989), p. 364.Cleveland, p. 204-205.

This professional hacker is absolutely reliable and I strongly recommend him for any type of hack you require. I know this because I have hired him severally for various hacks and he has never disappointed me nor any of my friends who have hired him too, he can help you with any of the following hacks:

ReplyDelete-Phone hacks (remotely)

-Credit repair

-Bitcoin recovery (any cryptocurrency)

-Make money from home (USA only)

-Social media hacks

-Website hacks

-Erase criminal records (USA & Canada only)

-Grade change

Email: cybergoldenhacker at gmail dot com