8.29.2011

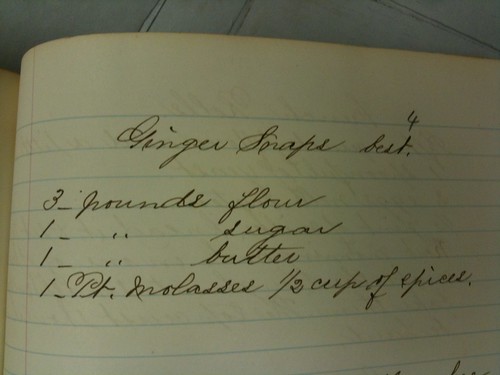

Mrs. Smith's Best Ginger Snap Recipe (from 1880)

Ms. Manami Matsuoka, Wofford's expert on Japan

8.26.2011

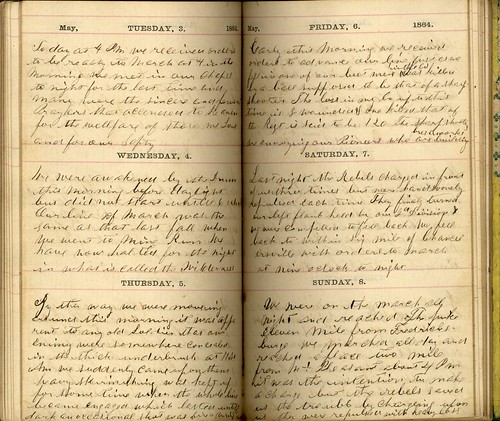

A Private's Wilderness

-Private Jesse Easton Bump, May 3, 1864

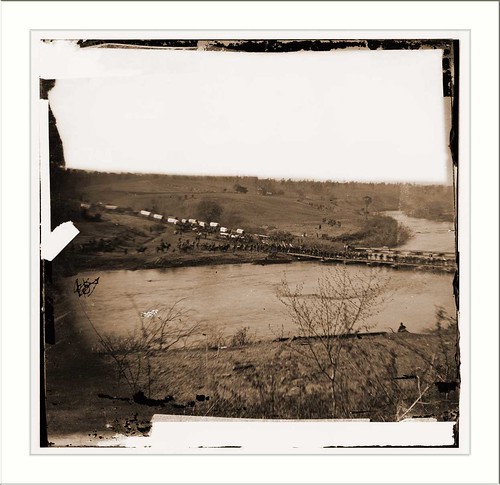

The Littlejohn Collection at Wofford College is home to the journal of Private Jesse Easton Bump, a Union soldier during the American Civil War. Bump was a soldier in the 119th Regiment, or the Pennsylvania “Gray Reserves.” He wrote a short entry almost everyday between September 1863 and August 1864. The entries below describe Bump’s experience during the Battle of the Wilderness which took place near Orange County, Virginia from May 5 to May 7.

The Battle of the Wilderness was the beginning of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign. The objective of the battle was to gain possession of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The Union and Confederate armies had spent the winter in close proximity; the Confederates were camped on one side of the Rapidan River at Mine Run and the Union army on the other side of the river near Culpeper.1Private Bump and the rest of the VI Corps left their winter camp and crossed the Rapidan River on May 4, 1864. He wrote in his journal,

We were awakened by the drum this morning before daylight but did not start until 6 o clock[.] Our line of march was the same as that last fall when we went to Mine Run[.] We have now halted for the night in what is called the Wilderness[.]

In order to avoid the strongly fortified Confederate camp at Mine Run, Grant decided the Army of the Potomac would have to fight in the wilderness surrounding the Rapidan River. The Wilderness was riddled with gullies and tangled underbrush. An individual would find the terrain difficult to move through, yet Grant ordered an entire army to march through it. Because of the wild landscape heavy artillery and cavalry (which were among Grant’s main advantages against the Confederates) could not be used effectively.2

By the way we were moveing [sic] around this morning it was apparent to any old Soldier that our enimy [sic] were somewhere concealed in the thick underbrush[.] at 11,30 Am we suddenly came upon them[.] heavy skirmishing was kept up for some time when the whole line became engaged which lasted until dark[.] an occasional shot was fired during the night[.]

By late morning on May 5, Grant sent VI Corps to hold the strategic Orange Plank and Brock crossroads at any cost until reinforcements could arrive.5 The battle was unlike any the soldiers had seen so far. The wild landscape made fighting more chaotic than usual; lines between divisions blurred among the tall trees and the dry forest caught fire on many occasions. Bump’s journal entry on May 6 details the number of men lost in the Wilderness:

Early this morning we received orders to advance our line first[.] as we fell in one of our best men (in the Co) was killed by a ball supposed to be that of a sharp shooter[.] The loss in my Camp to this time is 8 wounded one killed[.] that of the Regt is said to be 120[.] The sharp shooters are annoying our Pioneers who are building brestworks [sic]

By the end of the battle, about 15,000 Union soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing. The Confederates lost about 11,400.6

Neither side was able to gain a permanent advantage by the second day of fighting because everyone had trouble maneuvering and maintaining order.7 In a last attempt, Ewell ordered a surprise attack on VI Corps on May 6, but the Confederates quickly became disorganized and struggled to gain their objective. Bump recounted these events the next morning in his journal:

Last night the Rebels charged in front of us three times but were handsomely repulsed each time[.] They finally turned our left flank held by our 2d Division & we were compelled to fall back we fell back to within six mile of Chancelersville [sic] with orders to march at nine o clock to night[.]

As Bump states in his journal, Grant ordered the soldiers to prepare for a night march on May 7. The Army of the Potomac was to move to Spotsylvania,Virginia in order to gain an advantage: the open fields surrounding Spotsylvania would be better for fighting and, if held, would be important in securing Richmond, the Confederate capitol. Already exhausted from two days of hard fighting, the army marched all night to Spotsylvania where fighting continued.

- Hannah Jarrett '12

1 Joseph P. Cullen, “Battle of the Wilderness,” Wilderness and Spotsylvania, Harrisburg: Eastern Acorn Press, 1985, p. 4.

2 ibid.

3Cullen, p. 5.

4 Noah Andre Trudeau, “Battle of the Wilderness.”

5 Cullen, p. 9.

6 Cullen, p. 15.

7 ibid.

8.24.2011

Google Doodle Honors Argentine Author Jorge Luis Borges | PCWorld

The latest mysterious Google doodle honors what would have been Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges' 112th birthday. Aside from being a pioneer in the genre of magical realism, Borges also imagined some of the foundational concepts of the Internet, such as "hypertext," long before the dawning of the digital age.

8.18.2011

Old Bailey Trials Are Tabulated for Scholars Online - NYTimes.com

“The Old Bailey Online project has done a great service in making those sources widely (and costlessly) available,” Mr. Langbein [of Yale University] wrote in an e-mail. But he complained that the claims about data mining have “a breathless quality: ‘you can expect big things from us,’ but as yet it’s all method and no results.” He said that the new findings belittle the work of a generation of scholars who focused on the 18th century as the turning point in the evolution of the criminal justice system.

Mr. Turkel, who developed some of the digital tools, said that data mining reveals unexpected trends and connections that no one would have thought to look for before. Previous scholars “tended to cherry-pick anecdotes without having a sense that it was possible to measure all of that text and treat the whole archive as a single unit,” he said.

8.11.2011

The Trial and Acquittal of Frank James

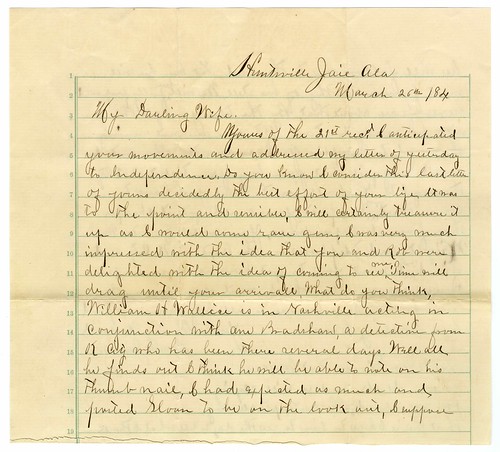

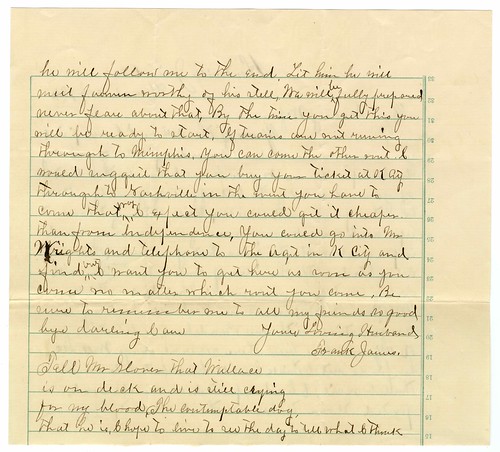

[TRANSCRIPTION:]

[recto]

Yours of the 21st rec’d I anticipated your movements and addressed my letter of yesterday to Independence. Do you know I consider this last letter of yours decidedly the best effort of your life. It was to the point and remember, I will certainly treasure it up as I would some rare gem, I was very much impressed with the idea that you and Rob were delighted with the idea of coming to see me. Time will drag until your arrival, what do you think William H. Wallace is in Nashville there acting in conjunction with one Bradshaw, a detective from Kansas City who has been there several days. Well, all he finds out I think he will be able to note on his thumbnail, I had expected as much and posted Glover to be on the lookout, I suppose

Your loving husband

Frank James

Tell Mr. Glover that Wallace

is on deck and is still crying

for my blood, The contemptible dog,

and that he is, I hope to live to see the day to tell what I think.

A notorious outlaw and member of the James-Younger gang, Frank James had been in prison since October 4, 1882, when he voluntarily surrendered to Missouri Governor Thomas T. Crittenden. James handed Crittenden his holster and said “Governor Crittenden, I want to hand over to you that which no living man except myself has been permitted to touch since 1861, and to say that I am your prisoner.”1 His surrender occurred six months after his brother and partner in crime, Jesse James, was assassinated by Robert Ford.

After his arrest, Frank James was moved to a jail cell in Independence, MO. His reception and treatment was hardly that of a dangerous criminal. He was allowed to wave at crowds from the back of the train that transported him. A reception dinner was held for him once he arrived in Independence. Supposedly, bankers offered to post a $100,000 bail for his release. In jail, Frank was allowed books, a comfortable chair, visitors, and whatever else he requested. He felt confident that he would not be convicted since the crimes he was accused of were committed years before. In the event that he was convicted, James was certain he would pardoned by the Governor. And in a bizarre turn of events, Frank James managed to be acquitted or pardoned for every crime he was accused of committing.2

While James was being held in Independence, he was charged with the the murder of Chicago detective Whicher (1874), the Independence bank robbery and murder of John Sheets (1869), the Blue Cut train robbery (1881), and the Winston train robbery and the murder of conductor William Westfall and passenger Frank McMillan (1881). James was acquitted on all accounts because the jury was not persuaded by the testimony of the prosecution’s primary witness Dick Liddell (also spelled “Liddil”), a former member of the James-Younger gang. The eloquent closing statements of John F. Phillips and Charles P. Johnson succeeded in convincing the jury that there was not enough evidence linking James to the crimes. By this point, James had won the sympathy of most Missourians due to his Confederate loyalties and his Robin Hood-like desire to avenge his family and former members of the Quantrill guerrillas for the crimes committed against them during and after the Civil War.3

During the war, James was a member of the Quantrill guerrillas, a group of pro-Confederate bushwhackers in Missouri. James’s involvement in the group had a significant impact on his criminal career. Many of James’s later crimes were in response to the way his friends and family were treated during the war. On one particular occasion, Unionists questioned Zerelda Samuel, James’ mother, about her son’s whereabouts and the location of the Quantrill guerrillas. They pushed her around, despite the fact that she was pregnant at the time. When she refused to give up any information, they tortured Dr. Reuben Samuel (James’s step-father) by hoisting him four times from the branch of a tree. He also refused to give away any information about his step-son’s whereabouts. Desperate for information, the Unionists chased and beat Jesse, Frank’s younger brother. In the end, Zerelda and Reuben were put in jail and Jesse’s hatred for Unionists increased, leading him to join his brother as a member of the Quantrill guerrillas.4

After the war, Frank and Jesse were harassed by members of the community because they were members of the Quantrill guerrillas. The Pinkerton Detective Agency was known to be involved in hunting the brothers throughout their criminal career. Allegedly, the Pinkertons were involved in bombing the James-Samuel house one night. The family heard a noise and went to the kitchen to discover that the west side of the house was on fire. Reuben saw a bomb and tried to shovel it into the fireplace. He was too late. The bomb went off, killing Archie James and injuring Zerelda (she lost her right arm). The continuous harassment of their family and friends can be seen as one of the leading motivations behind Frank and Jesse’s criminal behavior.5

The James brothers’ motivation for the Independence Bank robbery and murder of John Sheets was to avenge the murder of their friend Bloody Bill Anderson. Supposedly, the brothers had mistaken Sheets for Major S. P. Cox, whose troops had ended Bloody Bill Anderson’s career in 1864. Others believed that the robbers thought Sheets had somehow been involved in killing Anderson.6 As for the Winston train robbery and murder of William Westfall, Jesse James believed Westfall had been aboard the train that carried the Pinkertons to the bombing of the James-Samuel house. Similarly, the criminals announced that their attack on the train at Blue Cut was in response to Chicago and Alton Railroad’s participation in the reward offer for their capture.

After James was acquitted and released in Independence, he was immediately arrested again; this time for the Muscle Shoals robbery in Alabama. He was moved to a jail in Huntsville, AL, and on April 17, 1884, Frank was tried. Like the trail in Independence, Liddell failed to convince the jury that his testimony was reliable. Furthermore, the defense called to witness several people who claimed to have seen James in Nashville at the time of the robbery, which supported James’s alibi that he had been staying in Nashville under the name B.J. Woodson when the crime took place in Alabama. He was again found not guilty.

Upon his release, James was immediately arrested for the Rocky Cut robbery of July 7, 1876, but Governor Crittenden pardoned him. For good.

James spent the next thirty years doing various jobs; he was a shoe salesman, a ticket-taker at a theater, and a telegraph operator. Right before his death, he supported himself and his family by giving tours of the James farm in Missouri for 25 cents. He died at age 71, leaving behind his wife and son.

2 Michael J. Cronan, “Trial of the Century!: The Acquittal of Frank James,” Missouri Historical Review Vol. 1, Issue 2, January 1997, p. 134.

3 Cronan, p. 133-153.

4 Brant, p. 26-33.

5 Brant, p. 133-136.

6 William A. Settle, Jesse James was His Name: or, Fact and Fiction Concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977, p. 40.

8.05.2011

A new app about a King's book; A book about a King, his book

Written with a touch of the irreverent, Majestie is a shared biography: that of the first Stuart King of England (James I) and the Bible that goes by his name. It is part tabloid, part history lesson, part speculation; but it’s all James.

7.29.2011

New Books: Self-Expression in the workplace, Africa, and the Weimar Republic

Identity Economics suggests that people’s identity--who they choose to be and who they’re perceived to be--is the most important factor affecting their economic lives. This book is co-authored by George A. Akerlof, economics professor at Berkeley and 2001 Nobel Laureate in Economics, and Rachel E. Kranton, economics professor at Duke.

Identity Economics suggests that people’s identity--who they choose to be and who they’re perceived to be--is the most important factor affecting their economic lives. This book is co-authored by George A. Akerlof, economics professor at Berkeley and 2001 Nobel Laureate in Economics, and Rachel E. Kranton, economics professor at Duke.Choice review:

The evolution of economics as a science has taken many paths. The more traditional approach is to assume that when individual optimizing behavior is incompatible with the common good, it is because the assumptions of the perfectly competitive model are violated. Imperfect information, uncertainty, externalities, and collusion lead to market failure. Much less attention has been given to how social factors (the common good) motivate individual economic behavior. Akerlof (Univ. of California, Berkeley; Nobel laureate, economics) and Kranton (Duke Univ.) are eminently qualified to take this approach, given their many scholarly publications. They present this material in a very readable and entertaining way. Their findings are that economic behavior is governed by one's social category, by the norms of that social assignment, and by how one views one's identity in that social context. What might appear as irrational may be quite reasonable, given one's perception of where one is in a group. The authors are not advocating that the traditional economic approach be jettisoned but rather expanded to allow for self-identity. The fruitfulness of this is seen in real-world examples in organizational behavior, educational attainment, gender and work, discrimination, and poverty. Summing Up: Highly recommended. General readers, upper-division and graduate students, researchers, professionals. -- J. F. O'Connell, emeritus, College of Holy Cross

Ousmane Sembène: The Making of a Militant Artist by Samba Gadjigo (2010).

This book looks closely at the life, personality, and beliefs of Africa’s controversial “father of cinema” in the context of colonial and post-colonial African culture. The author is a french professor at Mount Holyoke College who specializes in French-speaking Africa and African cinema.

This book looks closely at the life, personality, and beliefs of Africa’s controversial “father of cinema” in the context of colonial and post-colonial African culture. The author is a french professor at Mount Holyoke College who specializes in French-speaking Africa and African cinema.Choice review:

This is the first biography of one of the most important African writers and filmmakers, a man who remains, as Gadjigo (Mount Holyoke College) puts it, "an unknown celebrity." The author intends to rectify this situation by retracing Sembène's trajectory from 1923 to 1956, the formative years in which Sembène (1923-2007) became a militant artist. By Gadjigo's own account, this is a careful "reconstruction" of the artist's life: because of the scarcity of written information about Sembène, the author has relied on first-hand oral testimonies. He provides numerous insights into Sembène's personal development by recalling little-known episodes of his life--episodes that reveal Sembene's major concerns as he expressed them in his work. In placing Sembène's experiences in their larger context, Gadjigo also re-creates a time period: for example, the reader gets a glimpse of what life was like for African dockworkers in post-WW II Marseille. This book is lively and the many quotes and personal testimonies make for an enjoyable read. Summing Up: Recommended. Upper-division undergraduates through faculty. -- S. Vanbaelen, Butler University

Women in Weimar Fashion: Discourses and Displays in German Culture, 1918-1933 by Mila Ganeva (2008).

Ganeva looks at how shifting fashion trends during the Weimar Republic allowed women to transform from objects of the male gaze to agents of self-expression. Ganeva is a German professor at Miami University, Oxford.

Ganeva looks at how shifting fashion trends during the Weimar Republic allowed women to transform from objects of the male gaze to agents of self-expression. Ganeva is a German professor at Miami University, Oxford.Choice review:

Informed by current research (in primary and secondary literature in numerous disciplines) and theoretical models, this study adds nuance to current understanding of German modernity. Arguing that fashion was an important area for women's self-expression in Weimar Germany, Ganeva (Miami Univ., Ohio) explores writings of female fashion journalists; a forgotten subgenre of Weimar film, the fashion farce (Konfektionskomödie); and the portrayal of the world of fashion in fiction. She shows that journalists combined the external attributes of the dandy with the critical eye of the flaneur to establish a unique voice of agency within German modernity. Aware that the autonomy established in the sphere of fashion in this period was a highly circumscribed one fraught with ambivalence, Ganeva also reveals the divergence between the generally glamorous representations and the lived reality by reconstructing the lives of models in Berlin. She concludes with an analysis of Irmgard Keun's novel Gilgi (Berlin: 1931), in which the protagonist turns to fashion as a sphere for creative independence. Ganeva's achievement lies in showing that these modern women saw themselves as active agents creating their own identify rather than as women subscribing to an objectifying male gaze. Summing Up: Recommended. Lower-division undergraduates through faculty; general readers. -- R. Bledsoe, Augusta State University

--Hannah Jarrett '12

7.25.2011

Lafayette + Huger = 19th Century BFFs

Raleigh March 2d 1825

My Dear Huger

We are so far progressed on our way to you when amidst the kindness which it is our Happy for to enjoy, we anticipate a consolation to our late sorrows by mingling them with these in which we have more deeply participated. Mrs Hayne Hamilton and [?] Have [?] me to inform you of our line of route. Pulled as I have been between the anniversary of Washington’s birth day and that of Bunker Hill, which I am the more bound to attend as the compliment paid to me is in my person confered [sic] upon the Revolutionary army, I Had no other way to visit the southern and western states, but to make it a very rapid tour. Contingencies may be anticipated, and actual calculations show that unless I gain a few days it will become impossible to comply with the initiative of the assembly and executive of the state of New York to when along the Canal to albany [sic] and through Vermont to Boston , a part of country. Which the obligation to embark for France somewhat sooner than we had intended would otherwise render it very difficult to visit. Under these circumstances I write to the intendant [sic] of Camden that we expect to be there on the 9h instead of the 8h and will be ready to attend [?] arrangement on the 8’ observing However that if they had been fixed for the 9th so as to make the alternative inconvenient to the citizens of Camden or the persons who are to be present, I shall conform to his wishes. The same observations I will make to you, my dear friend; it has been calculated we should be at Charleston the 13’ and Savannah the 18h. But if by a better calculations of the route, or acceleration of the mark you may forward as so as to make it possible to take our tour from pitsburg [sic] to albany [sic], it will enable me to perform a very pleasant and almost indispensable piece of duty which, if remaining

![Lafayette letter to Francis Huger [verso]](http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6125/5964178989_11887075d5.jpg)

[verso]

to be done would leave me with a remorse or greatly retard our reunion with the two united family which the loss of dear Mde de Tracy more justly desolated. Remember me to my old friends Pinckneys if you are with them. Most affectionately

your friend Lafayette

My companions beg to be remembered to you.Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette was born on September 6, 1757 in Chavaniac, France to an extremely wealthy family. He was a general in the American Revolution by age 19 and went on to be a leader of the National Guard during the French Revolution.

Lafayette’s parents and close relatives all died by the time he was 12 years old, leaving him with a large estate and inheritance. He married Adrienne in 1774, as his parents had arranged.1 Lafayette left to fight in the American Revolution on April 20, 1777. He departed from Spain disguised as a courier because the British ambassador wouldn’t allow him to join the Americans.2 Lafayette arrived in Georgetown, South Carolina on July 13, 1777. He met and stayed with the Benjamin Huger family for two weeks before travelling to Philadelphia to join the Continental Army. He was placed under the command of General George Washington, with whom he developed a close relationship throughout the war.3 After leading a successful retreat at the Battle of Brandywine despite being shot in the leg, Lafayette was promoted to General.4 Lafayette went on to defeat the British commander General Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781.

After the Revolutionary war in America, Lafayette went back to France and helped spark the French Revolution. On June 27, 1789, Lafayette joined the National Assembly, and, on July 11, he presented the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.”5 He was elected vice-president of the Assembly and later declared the commander-in-chief of the French National Guard. Lafayette fell out of favor in 1792 when the Assembly, which was made up of radical Jacobins, declared him a traitor because he supported constitutional monarchy.6 He fled France, intending to retire in America, but he never made it. He was captured by the Austrians and Prussians who were trying to end the revolution in France.

Lafayette was imprisoned from 1792 to 1797 for his involvement in the French Revolution. He spent time in the Prussian prison Silesia and the Austrian prison Olmutz. At this point, the Huger family played a crucial role once again. Benjamin Huger’s son, Francis, became involved in a scheme to break Lafayette out of prison. Huger and his partner Justus Erich Bollman would have succeeded if not for some miscommunication. All three were captured and returned to prison. Despite the failed attempt, Lafayette never forgot the loyalty and courage Huger displayed. Though Lafayette thought he would never see America again, he often thought of America while in Olmutz and was happy that America, at least, was successful in its quest for liberty.7

Then, in 1824, Lafayette was invited to visit America again. President James Monroe personally sent him an invitation on February 7, 1824. He wrote, “...as soon as possible, I may give the orders for a vessel of the State to pick you up at the port which you indicate and bring you to this adopted country of your youth, which has always retained the memory of your important services.”8 Lafayette’s main purpose with the “Farewell Tour” was to revive the Liberals’ political prospects in France by publicizing the lessons that America had learned about republicanism. Lafayette wished to show Europeans how a successful republic operated. Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette’s private secretary during the time of his tour in America, was in charge of sending dispatches to liberal writers in France who published the writings in newspapers and journals.9

The “Farewell Tour” lasted fourteen months, in which time Lafayette visited all twenty-four states. He left for America on July 12, 1824 on an American merchant ship called The Cadmus. He arrived in New York on August 16. In each town/city he visited, a crowd of people waited to greet him. There was a lot of pomp and circumstance upon his arrival: festivities, banquets, banners, etc. Lafayette would give a speech and visit old friends in each place before moving to the next. Among the many cities Lafayette visited, in his above letter he specifically mentions Albany, Boston, Pittsburgh, Charleston, Savannah, and Camden.

In Charleston, South Carolina, Lafayette met up with his old and dear friend Colonel Francis Huger as he promised in his letter. Levasseur writes about welcome that both Huger and Lafayette received:But of all these demonstrations of popular affection, what moved the General most was the touching and generous idea of the citizens of Charleston to have him share the honors of his triumph with his brave and excellent friend, Colonel Huger....When we entered Charleston, his fellow-citizens insisted that Huger take his place beside the Nation’s Guest in his triumphal carriage, where he shared with him the public’s felicitations and approbation. At the banquet, at the theatre, at the ball, everywhere in fact, Huger’s name was inscribed beside the name of Lafayette, to whom the inhabitants of Charleston did not believe they could express their gratitude better than by demonstrating equally deep gratitude to the one who had not been afraid to risk his life to set him free in the past.10

Upon his departure, Charleston’s city fathers gave Lafayette a gold-framed miniature of Huger. The miniature found a permanent home in La Grange, where it served as a constant reminder to Lafayette of his dear friend from South Carolina who risked his freedom trying to rescue him.11

*The Littlejohn Collection at Wofford College is home to three more letters written by the Marquis de Lafayette. The letters were written in 1801 and 1830.

- Hannah Jarrett ‘12 and Becky Heiser ‘11

1 Clary, David A., Adopted Son: Washington, Lafayette, and the Friendship that Saved the Revolution (New York: Bantam Books, 2007), p. 7-20.

2 Buckman, Peter, Lafayette (London: Paddington Press, 1977), p. 40.

3 Clary, p. 85-117

4 Clary, p. 115-117

5 Buckman, p. 143-144.

6 Spalding, Paul S., Lafayette: Prisoner of State (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2010), p. 5-6.

7 Spalding, ch. 4-6.

8 Levasseur, Auguste, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825, Journal of a Voyage to the United States, trans. Alan R. Hoffman ( Manchester: Lafayette Press Inc., 2006) p. 2.

9 Levasseur, xxiv.

10 Levasseur, 315-316.

11 Spalding, 234-235.

![Lafayette letter to Francis Huger [recto]](http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6121/5964736558_d2be79fb0a.jpg)